|

This article contains affiliate links... If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

​

When I first became a piano major in college, I worked like I had a fire lit under my bum.

I can't recall another time I extended so much effort in my life, I was practicing 6-8 hours every day - including many weekends - for years. But it makes sense: as a first-generation Korean-American, I come from a working class family - physical exertion was the only way. My professor lauded my work ethic, my colleagues - supposedly - admired my discipline and I progressed immensely through brute force alone. But anyone in their right mind would've hated my approach. They wouldn't just balk at the crazy amount of hours I put in, but dismiss my practice philosophy (if I even had one) as tedious and boring. To which I completely concur. Looking back at those days, I can objectively say I wasted more than half of those hours I spent practicing. If I had a time machine, you bet I would go back and do things completely differently. Fact is, the conventional, traditional approach - repetition after repetition a.k.a. no-painno-gain - is still the dominant one today. To succeed, you need bust your butt day after day ... month after month ... year after bloody year. If you put in the time, everything will work out. So suck it up buttercup, put your hours in and deal with it - that's just the way it is. Only it isn't. The truth is that it's not going to magically work out for you if you just put in the hours alone. The good news is that there's a better way, one that's less painful and way more fun. The key to practice that sticks is not endless hours of mental and physical exertion. It's using time-proven, science-tested strategies based on variety, maximum concentration and enjoyment. So in today's article, I'm going to share the concepts that have radically changed the way I teach and practice piano. If you apply these concepts, I'll bet you my left eyeball that you'll get incredible results - results you wouldn't have dreamed were even possible. Here's the gameplan: in each section, we'll go into depth on a single concept. I'll not only provide explanations and benefits, but examples of how I've applied each concept in my personal and professional life. I hope you'll be able to take what you learn here to craft your own personal, strategic, and fun sessions for piano success - whatever that means to you. Ready to have your mind blown?  How to Break Down Piano Practice

Question: How do you eat a pizza?

Answer: One slice at a time. You could be a smart aleck and say one bite at a time, but the point is you don't just inhale the whole thing - unless you're a competitive eater. Yet this is how most people approach work, and what's the result? Procrastination becomes our best friend and worst enemy. This is because our minds aren't built to deal with huge, massive projects in one go - we have a difficult time processing a ton of information at once. For instance, pay attention to how you feel when I mention:

The reason your eyes are glazing over is because it puts your mind in a sink-or-swim mentality. The solution is to small-chunk: divide your entire workload into manageable segments. This comes naturally for us anyway. For example:

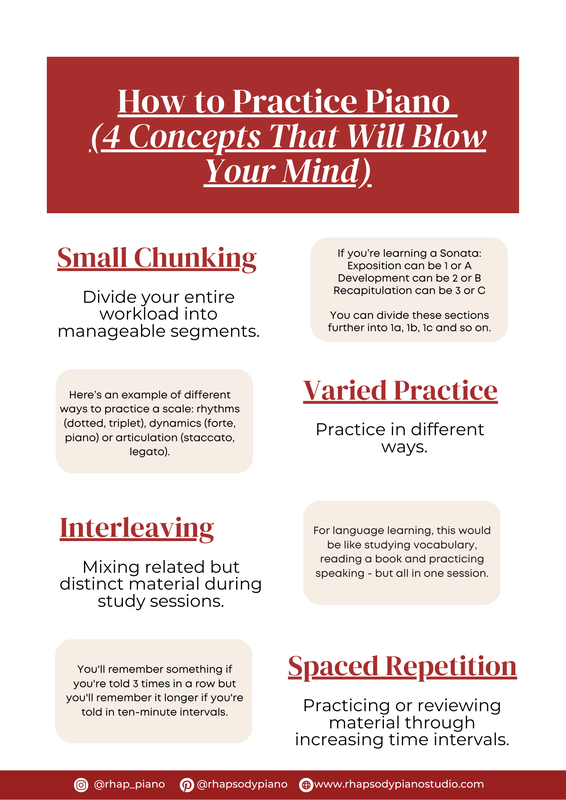

Stories have a beginning, middle and end. Songs have hooks, verses and choruses. Each house is built brick by brick. Small-chunking not only creates a structure that your mind can make sense of, but a process that is more efficient than the normal guns-ablazing, damn-the-torpedoes approach. I've used this idea to build many long-lasting habits over time. For instance, at one point in my life I was meditating up to 30 minutes a day. But I started with 5. My current stretching routine is a little over a half hour. Yet it began as 10 seconds (per stretch). Stephen King suggest the same for writing, which is to do so one word at a time. Pretend you're working on a sonata. Most students default to practicing the whole piece from beginning to end. Now, if that sonata was a table then this would be like putting all your attention on the surface: you can enforce the top as much as you want, but if even one of those legs are flimsy then the entire edifice will collapse. Practicing in small chunks strengthens each column and ensures your construct will stand on solid ground. Think of each leg as a portion of your sonata: the technical name of each part is exposition, development and recapitulation. But you don't even need these terms - you can simply use numbers or letters. For example:

Here's where it gets interesting. Now that you have your major (macro) sections, you can divide them even further (micro). If you're using numbers, then your exposition becomes 1a, 1b, 1c and so on. If using letters, it becomes A1, A2, A3, etc. Besides making sure your sonata is sturdy, here are some other benefits you'll reap by small-chunking:

Making these divisions are especially valuable when working from memory: when you memorize each chunk separately they become "signposts" to guide you during performance. It's kind of like including enough pit-stops on a road trip - even more paramount if you have a weak bladder. Now, a word of warning: don't mistake difficulty for attention-span. This is another reason why it's a bad idea to practice your entire piece from beginning to end - this results in a strong intro, mediocre middle, and weak ending. Once you've subtracted enough - created enough signposts and distilled a unit to a manageable nugget - then you add. Notes become measures, measures become phrases, phrases become a micro-section (A1, 1a), micro turns into macro (A, B, C, 1, 2, 3) and eventually you have the whole thing. Let's use technique as an another example. If you're learning a traditional 4-octave scale, start from the smallest unit. When I teach this to a student, this is the progression:

What about rhythm? No problem. We can even use this approach for one of the most difficult patterns - polyrhythms (2 different rhythms occurring at the same time). Just start with a single beat - play a triplet in one hand against 2 notes in the other. After this gets easier, add another beat. Rinse and repeat until you're able to do pull off an entire string. If you start small enough, anything is possible. Onto our next concept.  The Spice of LifeBruce Lee once said, "I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times." This is something everyone can understand: single-minded, undistracted effort. Due to my culture and heritage, I was basically indoctrinated into this work-till-you-drop mentality. Not that I'm ashamed of it in any way - I'm proud of the discipline I inherited working alongside my family in our businesses. So when I got serious about piano, I was like a hammer that saw everything as a nail - and my practice was just as straightforward: if 5 reps weren't enough I'd try 20, 50, 100 ... to infinity and beyond! But like I said in the beginning of this article, all that hard work led to ... bare results. It makes you wonder, why be so industrious if the returns don't justify the means? So what's the alternative to this nose-to-the-grindstone work style? The secret is to tweak Bruce Lee's original saying:

Allow me to introduce our next concept: varied practice. I came across varied practice in the book How We Learn, by Benedict Carey. It's a book you can't miss - the next 2 concepts I'll discuss are also from this book. Here's one of the studies: Researchers at the University of Ottawa observed 36 eight-year olds who were enrolled in a 12-week Saturday morning PE course at the local gym. They split the group into two. The exercise of choice was beanbag tossing. The first group was allotted 6 practice sessions. For each session, they were allowed 24 shots at a distance of 3 feet. But the second group varied their practice. They had 2 targets to practice on, one target from 2 feet and another from 4 feet away - this was the only difference. At the end of 12 weeks, the researchers had both groups perform a final test. The caveat was that it was from the distance of 3 feet, to which the first group was already accustomed. Before you object to the fairness of the test, check this out: despite the disadvantage, the second group still outperformed the first (3-feet only) group. As a Lakers fan, this makes me wonder how many more championships would have been won if Shaq varied his free throws. Anyways. This isn't limited to physical activities, you can also vary environments. A college student can use this on a smaller scale. Let's say they're struggling with a paper or project - in this scenario you can deploy the Grand Gesture. This idea comes from Cal Newport, author of Deep Work and other noteworthy books. In Deep Work, he shares how J.K. Rowling finished the last part of The Deathly Hallows by checking into the five-star Balmoral Hotel located in downtown Edinburgh. The hotel was not only her inspiration for Hogwarts, but provided a nice change of pace from house chores and loud kids. She ended up staying ... until she finished the book ... at a cost of more than $1,000 per night. Now, if your dinner is usually top ramen then you barely have the funds for a Motel 6. But on a smaller, more affordable level, you can retreat to the corner of a library or local cafe. You can also mix things up by changing the way you work. I once read that Ernest Hemingway wrote standing up. So what did I do? I purchased a standing desk and the change of pace has been super. It's nice to get off my butt as much as possible, considering how much time I stay seated teaching private lessons and practicing piano. And the change in physical posture has a clear, positive effect on my productivity. So we've covered beanbag tossing, changing locales and writing - now let's talk piano. Furthermore, I'll demonstrate the utility of varied practice with one simple pattern. Here are all the different ways you could practice a single scale:

Like small-chunking and the other concepts you'll learn today, varied practice is only limited by your imagination.  Productive Multi-TaskingWhen TiVo came out, commercials were instantly made irrelevant. All of a sudden, you didn't need to sit through endless advertisements. And smartphones have taken things to a whole new level. These devices have made things a thousand times more convenient, but that convenience comes at a price - the scattering of our attention. I mean, people can't even wait in line for one minute before zombifying themselves on their screens - swiping from app to app, switching from video to video. However, it might surprise you when I say this is the general idea behind our next concept: Interleaving. Out of all the concepts you'll learn today, this is one's my absolute favorite and I'm convinced you'll love after you give it a try. Interleaving is mixing related but distinct material during study sessions. If you were learning to cook, this would be like chopping vegetables, listening to a cooking podcast, reading a recipe book, and watching video demonstrations ... in one session. It's similar to varied practice. But whereas varied practice is more vertical - sticking with a single problem - interleaving is lateral, moving across different problems with the same goal. Instead of climbing up a ladder, you jump to a different one. Here's a second study from How We Learn. Researchers tested 2 different groups on a painting project/assignment:

Just like the last study, the second group (mixed-study) outperformed the first group (blocked-study) - 65% to 50%. The researchers ran this trial on a separate group of undergraduates with the exact same results. If we applied interleaving to exercise, it would look something like cross-fit or what's called a "bro set." Instead of repeating an exercise with rest periods, you immediately switch to a different one. For example, doing squats after a set of pushups, or jumping jacks after crunches. When I first discovered a love for books, I intuitively used this strategy to read for hours at a time. When I got bored with a book, or my concentration waned, I'd immediately switch to another one. Which is why I always had a minimum of 5 books on me at all times. Here's how I apply it to my language studies. I schedule my sessions using the pomodoro technique. Each block of time is spent on one of the following categories:

Ideally, I'd be able to do this all in one session but I usually sprinkle these activities throughout the day. You can take it a step further by interleaving un-related activities. In one session you could:

And there's no specific order to do these in - many times I'll just show up to my desk and do what I feel like in the moment. But perhaps the most important benefit is that it transfers to the real world better. It's like that saying about school, what you learn in the classroom stays in the classroom - the content you learn from a textbook doesn't automatically transfer to your real life. Canine enthusiasts know what I'm talking about. When you're training a dog, you need to put them in a variety of situations. Your pup might be an angel at home, but in a new place with all kinds of stimuli all that coaching will go out the window. This is also why so many of my students will say the same thing week after week, "but I played so much better at home." It's easy to rattle off successful performance after performance at home, but at a public venue it's a different story. So instead of controlling every scenario, interleaving introduces randomness, which is more like the real world. This grates against our nature because we're pattern-recognition machines we need an explanation for everything (even if there isn't one). But like Neo says in The Matrix, "there is no spoon." So here's how I use interleaving to practice. My regimen consists of:

For musicianship I could try transposing a Bach minuet into a few different keys, playing through chord progressions and working out some jazz harmonies. Technique consists of playing scales, etudes, and arpeggios but in a random order - or even jumping back and forth from scale to etude to arpeggio. Repertoire can comprise multiple genres as well as different levels of difficulty. But as much fun as I have in my own daily practice sessions, I believe my students get much more enjoyment out of interleaving. Here's what a typical lesson looks like:

Most times I'll follow a certain sequence, other days there's no preset order. The unpredictability keeps them on their toes and the momentum generated helps us fly through our lesson time - all while keeping their concentration at a maximum level.

The combinations that interleaving allows you, unlike my credit cards, are limitless.

Space, The Final Repetition

We're all familiar with the phrase, "don't just stand there, do something!"

But this final concept advocates the opposite, "don't just do something, stand there!" This is the spacing effect or spaced repetition. This is why:

Now, this time a story from How We Learn. In 1982, 19-year-old Polish college student Piotr Wozniak built a database of about 3,000 words and 1,400 scientific facts in English (he really wanted to learn the language). He experimented by structuring and scheduling the material in different ways. Soon, he noticed a pattern: after a single session, Wozniak could recall a new word for a couple days. But if he restudied it the very next day, that retention lasted for a week. And after a third review session (2 weeks after the first) he could remember it for almost a month. In other words, you'll remember something if you're told 3 times in a row - but you'll remember it longer if you're told in ten-minute intervals. Around my home, this is a natural phenomenon: my wife will hum the melody of a song she just taught a student earlier that day ... ten minutes later I'm humming the same (damn) tune subconsciously. Spaced repetition is by far today's most time-efficient learning strategy: you're able to learn and memorize better - and more easily - by spreading review sessions over increasingly longer periods of time. It's like an investment compounding, only it's your brain. Fluent Forever is an app that uses this to great effect. I practice with it daily and it's how I've been able to keep thousands of words memorized in a few different languages. This is something I naturally do with (good) books. If it's worth my time, I'll re-read a book after a spell. And almost every time I come away from that second reading knowing more. As a side note, there's an adage that many serious bookworms know about: you get more out of great literature the more times you re-read them. It's also how to not kill yourself as a writer: the most useful piece of advice I ever read was to just stop entirely when you get stuck and come back the next day. Yes people, giving up is an effective technique. Here's how I apply spaced repetition to piano lessons. First, I look at it from a micro level. If a student is having a hard time with a difficult passage, I'll have them practice juuust until they're near their "breaking" point. Right before they reach that moment, we'll work on something completely different. After about 5 minutes or so we come back to the very same passage and nearly every time you'll hear them say, "hey, it's easier for some reason." At which point you silently mouth, "spaced repetition." Second, the macro level. This is my go-to concept when preparing a student for a recital, especially if it's their first performance. For first-time recitalists, it's beneficial to schedule their mock performances as far ahead as possible since the wait periods in between practice rehearsals will be getting longer and longer (to utilize the spacing effect properly).

This lets us take full advantage of spaced repetition - the more cycles a student goes through, the better the result will be when they step on stage for the very first time.

This also works equally well, if not better, for memorization. Ever since I became a devoted spaced repeater (tempted to say space cowboy), I've been able to keep repertoire memorized with just a few review sessions per year! To see examples of how I do this, grab a copy of The Rhapsody Practice Guide - which is included in the Rhapsody Starter Pack (sign up for the newsletter and you'll be taken to a page where you'll receive it at a discount). However, this concept really shines when introducing brand new material to the student. As a teacher, if you internalize this concept and are able to teach it well, you can use this for everything:

And what's even more ridiculous ... they don't even have to practice at home. I once had a student who was really bad at note-reading (almost as bad as my sightreading). For the life of me he would never practice flashcards at home no matter how many times I begged him to. So we only did them at the lesson - it took him 6 months to read basic notes. For 6 whole months, we did flashcards once a week. It frustrated me to no end, but the point is we eventually got there. Moving on. Here's a sample plan involving scales - but remember you can extrapolate this to just about anything. Keep in mind this is a situation where the student has never played a scale before. I'll have them play a one-octave scale once at the lesson (with one hand). Then they'll play it again ... a week later. If all goes well, we'll do more spaced repetition within the lesson. If we're not at this point, we just wait another week to try again. Once they're past this stage, I can then assign the student that scale to practice for the entire week. But I only do this if I'm positive they can play correctly. This is has to do with encoding success practicing correctly from the start. It's also because I give them no instructions whatsoever. Seriously. If you opened up their instruction book, all it would say is, "technique: one scale, one octave, hands separate." Then we baby-step this process until they're able to practice both hands to at least two octaves. Sometimes the lazy approach pays off.  Less Is More

The mainstream advice for success is to add, add, add. But doing this turns you into the "busy" person at the office - having a million things on your plate while contributing little value.

But it's really about elimination - what not to do. As someone who spent their entire childhood in the family business, this was a hard pill for me to swallow. I always believed that you could achieve anything as long as you worked hard for it. But I took a look in the mirror one day and realized the results didn't justify the time I (wasted) spent.

Most people will take what they read today and promptly forget it. They just don't want to believe you can get more done with less effort.

I hope you're not one of them. Toiling by the sweat of one's brow says one thing, it's my way or the highway. But what's the point if that highway leads you off a steep cliff? Isaac Newton once said he succeeded because he stood on the shoulders of giants. The smartest way to achieve success in this world is to take the lessons that great people before you have learned. In fact, to go through the same difficulties even though it's avoidable is stupid. If you got something out of today's article - heck if you even read this whole monster of a post - it means you value your time. Look, I love hard work as much as anyone else. It feels great to be productive, to be exhausted at the end of the day knowing you left nothing on the table. But between practicing hard and practicing smart, I'll choose the latter every single time. Process over results. Yes. But that process is useless if you're not getting outsized returns. So here's a toast, cheers to the preposterous results you'll get if you use what you've learned today. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|