|

This article contains affiliate links... If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

Kurt Vonnegut once said, "When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth." Well, trying to figure out what you want to practice on piano can feel the same way.

For example, when I ask parents - my students are mainly children - what their piano goals are they usually say, "I just want them to enjoy lessons and practice every day." That's like saying you want food for dinner. Declaring such a vague goal is a symptom of not knowing how to properly set one. Okay smart guy, then how do you go about this? Well, the first challenge is understanding you need to sit down and spend some time at your desk. If that sounds easy to you, it's not. You will encounter plenty of resistance and be tempted to just "wing" it - DON'T DO THIS. "Going with the flow" seems like the much more attractive option. But it's because it takes zero mental effort. And as Stephen Pressfield says: what we resist will persist. Don't run from that resistance, it's actually a compass that will point you in the right direction - lean into it. So if it's your first time developing a plan, understand that there's no way to avoid that initial discomfort. But hey, since you're reading this article this means you already have a head start.. And believe me, one day you'll actually look forward to planning sessions. You'll look back and realize that taking the time to plan is what allowed you to execute your practice and achieve your goals flawlessly. Now, at this point you might be wondering how much time you need to spend planning. We'll cover that near the end of this blog post. First, let's talk discuss why writing down your goals is so important.  Things to Practice on PianoWhy You Need Goals

Not setting goals is like trying to shoot an arrow into a bulls-eye ... blind-folded.

With a strategy like that, all you can do is cross your fingers - and hope you're not a contestant in the next Squid Game. But when you set a goal, it becomes a constraint (like a deadline for a project). And the more specific your goals are, the larger the targets become (easier to hit). With an effective plan, you'll have better clarity of focus since you won't have to spend your concentration on spur-of-the moment decisions. It's like planning your meals for the week - I do this with my wife every Sunday. If we don't, we get caught in decision hell: what do you want to eat? No, what do yoooou want to eat? NO, WHAT DO YOU .... kill me now. Also try and plan to the last detail, this helps you deal with the unexpected. When I write my goals I do it with the intention that things aren't going to go according to plan. So when something unforeseen happens, it's easy to get back on track since I expected it. It's like a battle plan, the most successful generals in history were the ones who planned for every positive and negative scenario. Recording your goals has another notable benefit. Just the mere act of writing your goals, or making notes, helps you utilize the Zeigarnik Effect. This theory states that just by merely writing something down, you decrease the amount of useless thoughts that occupy your mind. In the book How to Take Smart Notes, we learn about the origin of this phenomenon: psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed waiters had an uncanny ability to remember everything customers ordered. But as soon as the diners left, the waiters were able to promptly forget everything. Based on this, she later developed the idea that open tasks will occupy your short-term memory until completed. This explains why we're so easily distracted by unfinished tasks and thoughts - to combat this all you need to do is write your tasks down. Not doing this means your brain will be full of distractions while you practice. When you write down everything you need to, your mind is clear and sharp. Now, I suggest taking it a step further and doing this for tasks outside of your piano regimen. If you don't do this, it won't matter if you have all your musical goals written down - there's always a chance things in your personal or professional life will butt in. David Allen's Getting Things Done is the book to get for this. Timeframe

Before we discuss what to practice on piano, let's talk about time.'

As in, how long should the preparation phase be? Take a cue from Ultralearning. The author, Scott H. Young, provides a useful framework: 10% of the total time spent on research. So if you plan on spending 100 hours on practice, you'll use 10 hours of that to plan. Another thing he says is if research is helping, you can always do more of it. And if it's not, less - spend more time practicing. Then, once you've done enough research and you're able to put your plan into action - decide on your timeframe. How long will it be before you conclude whether or not something's working for you? If it's your first time doing something like this I suggest going with a shorter deadline. Try one month. Once it's over sit down, analyze your progress, make adjustments and continue. However, the timeframe that works perfectly for me is 90 days. It works out to 3 months, what's known as a "business quarter." But I don't only check my progress at the end of each quarter. I analyze my results at least once a week and once a month, it's like having pit-stops on a long road trip to your destination. Another question you might have is, how do I measure success? I've talked about this before, but what works best for me is tracking my time. Knowing exactly how many hours I spend on each activity gives me enough data to make important decisions. It also keeps me away from a results-oriented mindset: my week-to-week, month-to- month goal is simply to not fall behind on my quota of time spent. But the meta-goal remains the same: I execute my plan for the entire 3 months, come hell or high water. What to Practice (Skills)Things to Practice On Piano (Skills)

Now that the planning phase is out of the way, what next?

Well ... what do you want? Do you want to get better at note reading? Learn to play by ear? Improvise? The list seems endless and if you have no idea where to start, let's reference Ultralearning again: learning projects are either "instrumental" (professional) or "intrinsic" (personal). Do you want to eventually make a buck and gain recognition for your talent or do you want to keep piano as a hobby for pure enjoyment? Instrumental skills move you forward professionally. This is like a makeup artist taking a Hollywood set design class or a stand-up comedian studying improv. Side note: it doesn't have to be exactly related to your field of expertise. There's a domino effect: what you learn in one field can affect another. And it's also how to overcome what's called domain dependence. I bring this up because an unrelated goal might become a related goal later in life. For example, you might think studying theory is useless - but if you plan on being a public school teacher, what if you're suddenly instructing a music class one day? It's far from reality: I know of one instance where a music teacher had to do double-duty as a basketball coach. On the other hand, intrinsic skills are things you do for pure enjoyment: fun activities without a care for professional advancement. This could be like becoming fluent in a language just because you want to. In fact, if you want to keep it fun I would argue to do exactly that - the best way to kill a passion is to turn it into a job. If you go to church, you might volunteer to be your choir's accompanist. Or maybe you just want to jam on the keys with your friends in an amateur cover band. Perhaps even compose your own music without the intent of publishing anything. Ever. Furthermore, don't make the mistake of thinking intrinsic goals are less valuable than instrumental. There are many hobbies I have that I don't make a dollar from but increase my general sense of well-being - which then creates more fulfillment in my career.  It's a Fine Line

In the next section, I have plenty of suggestions for you on what to practice on piano. But what you'll notice is that I haven't categorized any of these activities as intrinsic or

instrumental. It's because, at least to me, it doesn't matter. Personally, I don't view intrinsic goals as different from instrumental goals. I don't care whether or not something advances my career, I learn for the sake of learning (improvement). I don't have a lot of time to practice these days, but I still plan on becoming the best pianist I can possibly be. Whether or not I become a professional, my goal is to continue to work on my craft until the day I die. Perhaps I'll be as good as an actual concert pianist someday. But whether or not I make it, I don't care. You don't have to agree with me, it's just my personal frame of mind. And I not only take this approach with piano, but with everything I'm learning in life. It's what Cal Newport calls the "craftsman's mindset." With my blog, I want to be the best writer I can possibly be. With foreign languages, I want to get to the level of reading scholarly articles. Again, the whole point isn't to actually reach any of these goals, it's the striving that I enjoy. It keeps me connected to the process - doing the work is its own enjoyment. So remember, whether a skill is actually intrinsic or instrumental boils down to your attitude. You decide whatever that means. Things to Practice on Piano (Suggestions)

Now, here are some ideas on what to practice on piano.

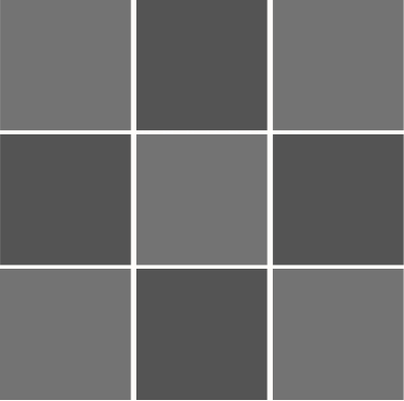

To make it easier, group activities into 4 categories:

With technique, you could practice the most fundamental patterns in all of music: scales, arpeggios and chords. You'll want to take it a step further and play them in every key. Otherwise you'll hit a wall when you get to an unfamiliar one. Another way to improve your technique is through study of advanced repertoire - practice the greatest composers of whatever genre you choose (baroque, classical, romantic, impressionistic, modern, etc.). Often, the music is difficult enough that your technique will improve without needing to do technical exercises. For note reading, you can practice flashcards and sheet music. To get better at playing by ear (ear training), listen to a variety of music. It's a great way to discover different styles, as well as understand different musical "languages." Studying harmony helps too: with enough practice you might be able to identify certain harmonies or chord progressions in the musical genre you're learning. Transposition is also a good skill to learn. After all, if you really want to be able to play by ear you need to be able to play songs in any key. Lastly, study theory to get better at musical analysis. That's only if you want to understand the "grammar" of music - how music is constructed, and so on. This is especially important if you plan on writing your own music someday - yes, all music follows certain "laws" of composition as does (good) writing. Side note: remember that when you learn the rules, you'll know when to break them. Once you've decided on your materials, read this article. You'll learn useful practice concepts to supercharge your progress. Conclusion

As the stoic philosopher Seneca once said, "luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity."

Don't fall for those stories of overnight success, which are mostly based on pure luck. Instead of leaving it to chance, you can change your life through effort - it just takes a lot of meticulous planning. But the sooner you start, the easier it will be. This will help you take the long-term view. The farther you're able to look out, the clearer the trajectory of your plans will be. And from there, all you need is to take the smallest action day after day. Then repeat a thousand times. Of course, that's easy for me to say and difficult to put into practice - but the only thing that makes it difficult is giving up. Or not even starting in the first place. So take that first step. Over time all your effort will start to slowly compound. One day you'll look back and realize how far you've come, all the while thinking - why didn't I do this earlier? Happy Practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

4 Comments

This article may contain affiliate links. If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

You know the feeling well: sometimes you remember things easily, other times it's on the tip of your tongue ... and it drops off a cliff.

Why does it sometimes feel facile, and at other times like your brain is malfunctioning? It's not like you've ever gotten advice on this either. School definitely doesn't help, all they'll tell you is to put more "effort" into it.

As with most things in life, we've been falsely conditioned.

We've been taught that to memorize is like taking a blunt object and trying to repeatedly "hammer" a fact into your mind.

And when this approach doesn't work? They say you're not trying hard enough.

But exerting more effort isn't the solution. What's worse is feeling like you have an inferior memory, that no matter what you won't be one of the "gifted" ones. Look, it's true that some people have a naturally good memory. I've been told mine is pretty abnormal - a question I always get is how did you remember that? That was years ago! Still ... memory is like reading music notes, learning sheet music, or practicing rhythm - it's a skill anyone can improve. They don't understand - it's not the person, it's the method. So if you've ever blamed yourself for having a "bad" memory, please stop - you just haven't been taught how to memorize. Today, I'll show you a foolproof method to memorize any song or piece easily. It's a method I've taught successfully to every single one of my students. And it'll work for you, how does that sound? But before we get to that, first we must dig deeper. It's because memory is not as simple as people make it out to be - it's actually quite the complex topic. Once we deepen your understanding, you'll never see memory the same way again. Here's what we'll cover:

Next, be careful what you wish for. How to Memorize MusicThe Curse of Memory

In the book Moonwalking With Einstein author Joshua Foer shares a story about a Russian journalist named Solomon Veniaminovich Shereshevsky (God that was hard to type).

Let's just call him "S."

He had a major problem. On a typical work day, his boss would blurt out assignments in rapid-fire to S and a roomful of his colleagues. Over time, bossman noticed that S would simply watch and listen - he never took notes. After many days of observing this behavior, he eventually became livid. He took S aside one day and tore into him, berating him to take the job seriously. What happened next was ... incomprehensible. After the boss finished his rant, S calmly proceeded to repeat every single detail of that morning's assignment. Word for word. You see, S's problem was that he could easily memorize anything. I fail to see the problem, you might be thinking. Surely, EVERYONE would kill to have a memory like that! No. They wouldn't. This superhuman feat came at a price, here's how it worked: everything S ever heard had its own color, texture ... even taste. In his own words, sounds evoked a "whole complex of feelings." Some were "smooth and yellow" while others were "orange and sharp as arrows." A voice itself could be "crumbly yellow." This turned out to be a curse: he couldn't think figuratively. Poetry was impossible for him to read, even simple stories were overwhelming (he couldn't stop visualizing). Imagine going to an ice cream shop. The cashier opens his mouth to ask what flavor you want ... and out flows a rainbow of molten lava. This was the price he paid for his stupendous memory. It wasn't that he could remember everything - it's that he couldn't forget. This explains why we can't - and shouldn't want to - remember everything. The true nature of memories are that they're supposed to decay over time. So the next time you get frustrated because you can't remember what you just studied, realize it's only natural. Next: a detailed look at the process of forgetting.  How Forgetting Works

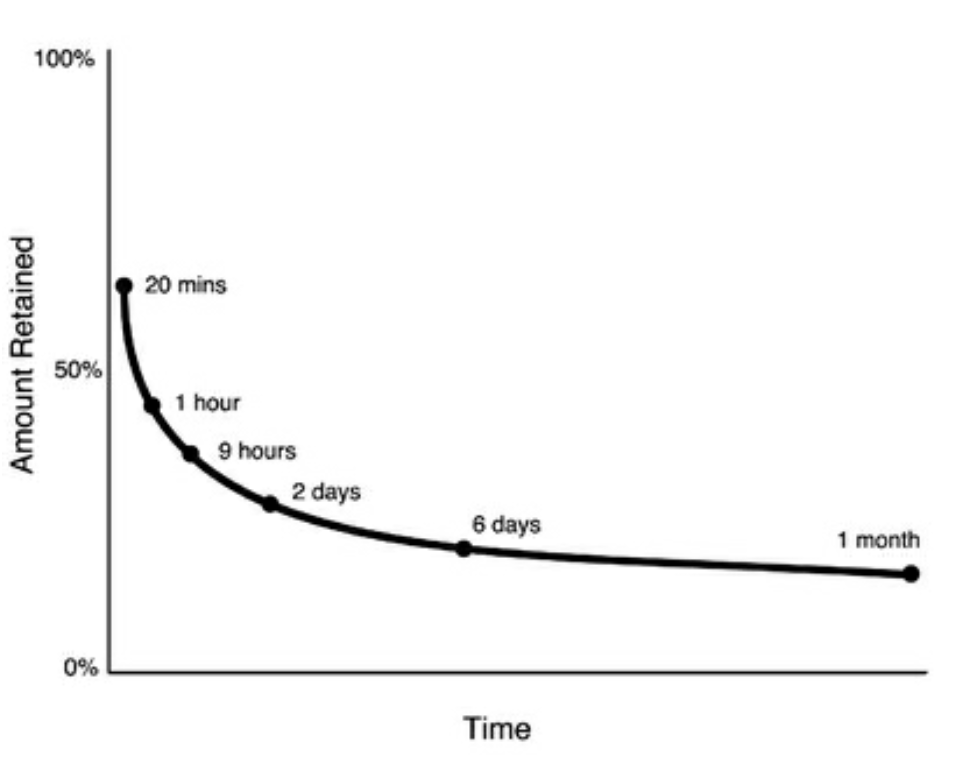

Hermann Ebbinghaus, a German psychologist, set out to understand the process of why we forget.

He spent years(!) memorizing 2,300 three-letter nonsense syllables - think GUF, LER, NOK - over varying periods of time to see what and how he forgot. Thanks to his masochistic research, we have one of the most famous images regarding memory - the "forgetting" curve:

No matter what he did, the results were the same:

For regular folks, they forgot 90% of what they studied within 3 days ... the majority of this happened within the first few hours after class or study sessions were over. From this we can conclude the brain isn't some machine with infinite storage. To err is to be human and to be human is to forget. Instead of thinking of forgetting as a flaw, realize it's actually a built-in feature. Next: the types of memory. Types of Memory

According to John Medina - author of Brain Rules - we have 2 types of memory:

Additionally, memory is short-term or long-term.

Now, whether something is memorized depends on two things: Automatic vs. Effortful processing. Automatic processing takes minimal effort - you're able to easily recall a physical location with lots of information (what came before and after). An example would be a memorable, meaningful experience such as your first kiss or the best birthday you ever had. This also explains why traumatic experiences are so hard to erase - but let's keep things positive here. On the other hand, effortful processing requires deliberate, conscious and energy- burning labor - like trying to remember your pin code or password to access your online bank account. So understanding what (information vs. procedure) you need to memorize can affect how (automatic vs. effortful) you do it. Side note: the tactics I'll show you later have more to do with memorizing repertoire. If you want to memorize "skills" - like reading sheet music or learning technique (scales, etc.) - then the traditional approach probably works better (rote learning). These types of skills require drilling (rep after rep), though there's still a smart way to go about this - perhaps I'll cover this in a future blog post. Next, concepts that teach you how to remember. How to Remember

Here's an iron rule to follow in order to make memorization as easy as possible: encode whatever you memorize as richly as you can.

Remember that "S" was able to memorize everything easily thanks to the elaborate, and baffling, images he created. We'll use that principle to harness some of that power for our benefit.

One way to do this is with vision - our strongest sense. In this blog post I mentioned a study in which wine experts from the University of Bordeaux failed to tell that the red wine they were drinking was actually white wine (dyed red). Even for these oenophiles - Bordeaux! - what they saw overrode all of their other senses. Since vision also takes up about half of the brain's processes, it's safe to say we learn better with images: in Brain Rules, tests that showed people could remember 2,500 pictures with at least 90% accuracy several days later! And this is how "memory athletes" are able to ingrain hundreds of sets of random numbers and letters by heart. For example, the number 8 could represent infinity. The number 2 resembles a swan. Thus, an image for 82 - infinite swans. So the next time you memorize repertoire, you might try visualizing a story. A great piece to try this on is Schumann's "Carnival" - every movement represents a scene or character. However, vision isn't the only way to memorize. A second method is retrieval. From the book Ultralearning, by Scott Young, an example of this is known as free recall. Imagine reading or viewing information, then immediately taking out a blank sheet of paper to write down everything you can remember. It's like elaborate coding, but the main reason it works is due to cognitive strain. This is related to effortful processing (mentioned earlier) and explains why most people will avoid this tactic - it feels horrible. But remember, difficulty is actually a reliable indicator: if it feels challenging, then you're doing it the right way. Lastly, chunking is an additional concept to aid memory - I use this in piano lessons all the time. Foer describes chunking as "a way to decrease the number of items you have to remember by increasing the size of each item." So HEADSHOULDERSKNEETOES becomes HEAD, SHOULDER, KNEES, TOES. ​Another example is the phone number (area code, 3 digits, then 4): 1234567890 = (123) 456-7890. This is also how chess grandmasters recall a seemingly infinite amount of moves: they chunk actions or strategies into sets they can use during games. However, when pieces are randomly ordered - instead of placed according to the "rules" of chess - the grandmasters' memories become no different than an amateur's. Why? Because chunking only works in context.

SF participant in memory experiments (no relation to S), memorized random numbers this way. When he saw 3,492 he translated this into 3 minutes, 49 point 2 seconds.

Since he was an avid runner, this worked because it represented a near world-record mile time (context). So when you chunk your music, remember that to engrain it into your memory as permanently as possible, it must be meaningful for you - whatever that entails (it's different for everyone). Now ... time to show you how to not forget.  How to Not Forget

Spaced repetition is my most reliable, consistent method to memorize anything - and it also works for all of my students (any age, any level).

It's based on this principle: you'll remember something if you're told 3 times in a row, but you'll remember it much longer when told in ten-minute intervals. This works because spaced repetition is like retrieval: it depends on cognitive strain. If you tried re-memorizing something within a few seconds or even a few minutes later, it's a lot easier than trying to recall that fact 30 minutes or an hour later. Ironically, people discount this strategy because it feels difficult. They'll stick with the more familiar method even if it's not effective - since it's more comfortable to them. But you know better by now. This is yet another nail in the coffin for the traditional school approach: rote repetition doesn't work because you not only short-circuit the natural process of forgetting, but also completely bypass mental effort. By the way, I'll show you how I combine spaced repetition with chunking in the next section. Now, suggestions on how to use spaced repetition. You can practice within a session or over the span of a longer period of time. For example, try memorizing at the beginning of your session. Do it again in 10 minutes and one last time 20 minutes later. Over the course of a week try memorizing on Monday, again on Tuesday and then a few days later on Friday. You can get to the point where you only need to practice memorization once a month or even once a year. One caveat: lengthen the period of waiting time when it's easy and shorten it when it's difficult. You can also easily move memories from short-term to long-term. It's a simple procedure:

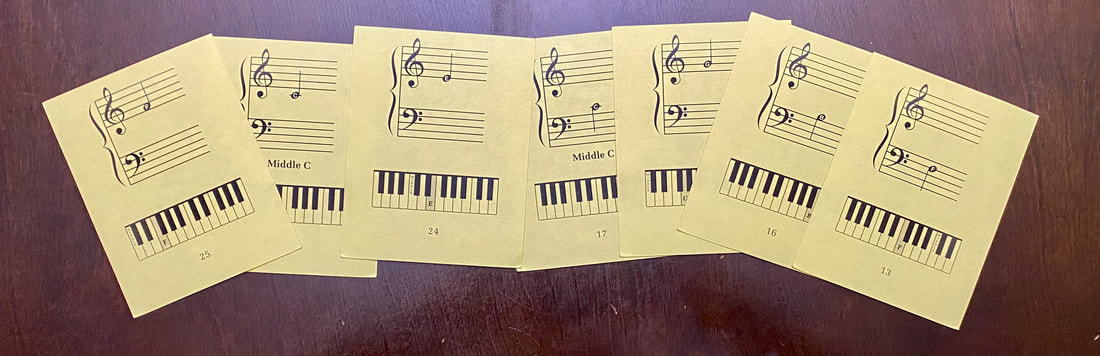

Play a chunk of music from whatever you're practicing then immediately cover up your sheet music and play it again - this is step 1 (with sheet music, without). When you do this enough times - and "space" your sessions out - it becomes a long- term memory. How do you know when this happens? You'll know this is the case when you're able to recall each chunk from memory without the sheet music. Here's how I do this in piano lessons:

The student might literally only see a flashcard with the letter C. He or she will then have to try and recall that section from memory and play it on the piano. If this sounds difficult to you, it is. But only at first - once they get more practice they're able to pull off this feat on a regular basis. But don't forget, even if you can successfully play from memory you must play it again with the sheet music (step 2: without sheet music, with). DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP. This is because you always need to verify what you've memorized. If you don't do this you run the risk of altering what you remember over time. The danger in not doublechecking your work is you might be playing something entirely different months later without even realizing it. There's nothing worse than not knowing what you don't know. Auto-Memory

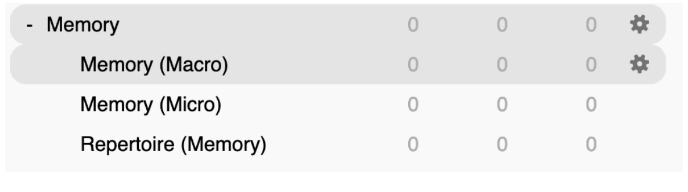

Now let me show you how to use Anki to put memorization on auto-pilot.

Chunk sections on 2 levels:

Macro represents the largest sections. For a story this would obviously be the beginning, middle and end. This is similar to a sonata - exposition, development, and recapitulation. Of course, every piece is different. But once you figure out the macro sections, label them with a letter. Sonata:

Then take each macro section and divide further into micro sections:

Once you've divided up all the sections, open up Anki and create "decks" at 3 levels:

Each chunk becomes a "card" for the appropriate deck (micro, macro, repertoire). Once you input each card, memorization is thoroughly taken care of since you've accounted for every level (bottom-up).

This is your foolproof, repeatable method for memorizing anything - check out this video for a live demonstration. Time to Say Goodbye

I used to believe memory was just like most things in life: to be conquered through brute force. But as I got older, I realized there was a ceiling to the effort I put in.

You can't solve everything through exertion alone, trying harder doesn't always work. Yet you can develop a strong(er) memory through correct practice and strategy - by working smarter, not harder.

And now you have the roadmap to do so, a process that can be replicated and used by anyone.

But it ain't easy, it'll take a few review sessions to fully understand the concepts you've learned today to put them into action.

And that's the point - if it was easy than anyone could do it. Take the road less traveled. Spending more time than necessary is just silly, don't put yourself through unnecessary difficulty. It's not just about looking cool - effort only matters if it leads to measurable results. I'll leave you with an important question, one that led me to develop this process: is there a better way to do this? This question helped me not only solve the problem of memorization, but develop countless frameworks to make my life easier. It's a powerful question because it taps into your curiosity, and curiosity is the superpower that can change your life. Remember to add a dash of imagination and you can overcome any challenge.

Hope this helped and happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

This article may contain affiliate links. If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

In my experience, there are 2 kinds of students: those who have natural rhythm and those who don't. And as I mentioned in the last blog post, some students excel at reading sheet music while others struggle.

Rarely do I come across a unicorn who's good at both. When I do, I thank my lucky stars - because there's less work for both of us to do. There are also students who practice and don't practice - a story for another time ... But rhythm isn't something you have to be born with, it's a skill anyone can learn. All it takes is the right approach. What makes learning rhythm challenging? Let's use dancing as an example. Now, in NO way am I saying dancing is easy. I admire the way a seasoned professional slides gracefully across a dance floor - while I look more like Jackie Chan. Anyways ... the point I'm making is that with dancing you just need to focus on physical choreography - again, NOT an easy feat. But when you play a musical instrument, there are auxiliary elements involved:

There are more precise motor skills to pay attention to. You have to take what you see on the page and decide which of the 88 keys you're going to press ... all while using the correct fingers to play the proper combinations of patterns.

And that's without keeping an (often) intricate beat. That's a lot to take in.

So rhythm on the piano is more mental, like solving a complex problem. Compare this to dancing where you just focus on the correct movements (again, NOT easy).

But the actual problem is trying to do too much all at once. The goal isn't to be perfect at everything, it's to practice internalizing the beat. And to do that, you need to find methods that make this as easy as possible. To that end, I'll share the strategies and tools that will help you succeed. First, a rhythm primer - you gotta have the basics down before we get to the good stuff.  How to Learn RhythmRhythm Primer

Now, this is just meant to be a rudimentary guide. Even so, it's all you need to get started - once you have the right tools and resources, you'll have everything you need to learn any type of rhythm you'll encounter.

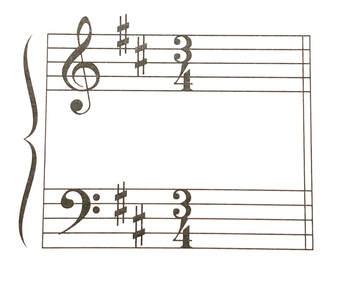

Let's start with the time signature:

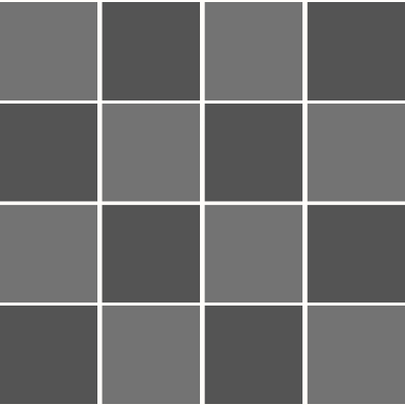

The top number represents the number of beats within a measure:

Change the number and you change the number of beats.

And so on. The bottom number is a bit trickier to understand, because it's not actually a number. It represents the type of note which receives a beat. For example:

So instead of thinking of a digit, you want to imagine the actual note (symbol) itself. Here are some more examples to help you put it together:

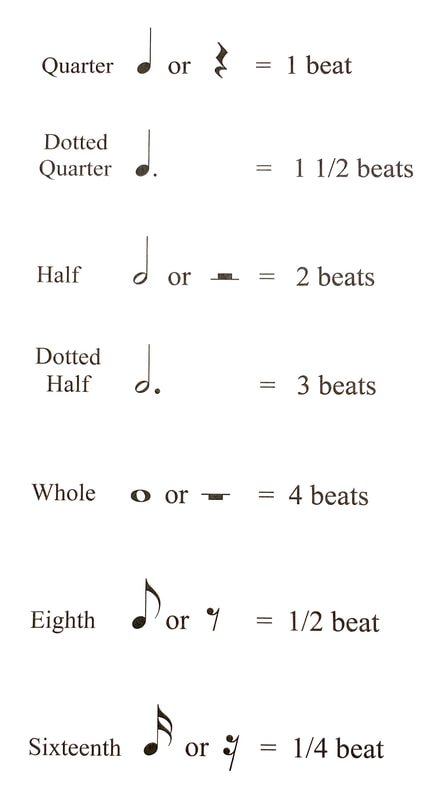

Lastly, the type of note value also determines the pulse of the music - if this is confusing to you, then wait until we discuss subdivision in the how to practice session. Speaking of notes ...

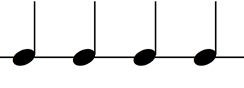

These are all the basic note values.

And regarding rests... do NOT think of them as pure silence. It's a mistake a lot of my students make, doesn't it mean to just stop and not play anything? NO. Think of rests as "silent notes." The rhythm carries on whether or not there is sound. And that's it, the basics of rhythm in a nutshell. No need for additional research - just get started. But before you gather the right tools and put the right plan into action, you first need to avoid the most common mistakes. Mistakes

Throughout my years of teaching, these are the patterns (bad habits) I've noticed:

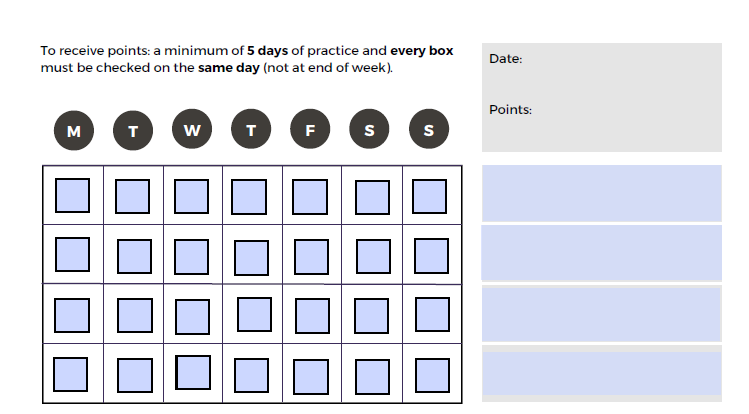

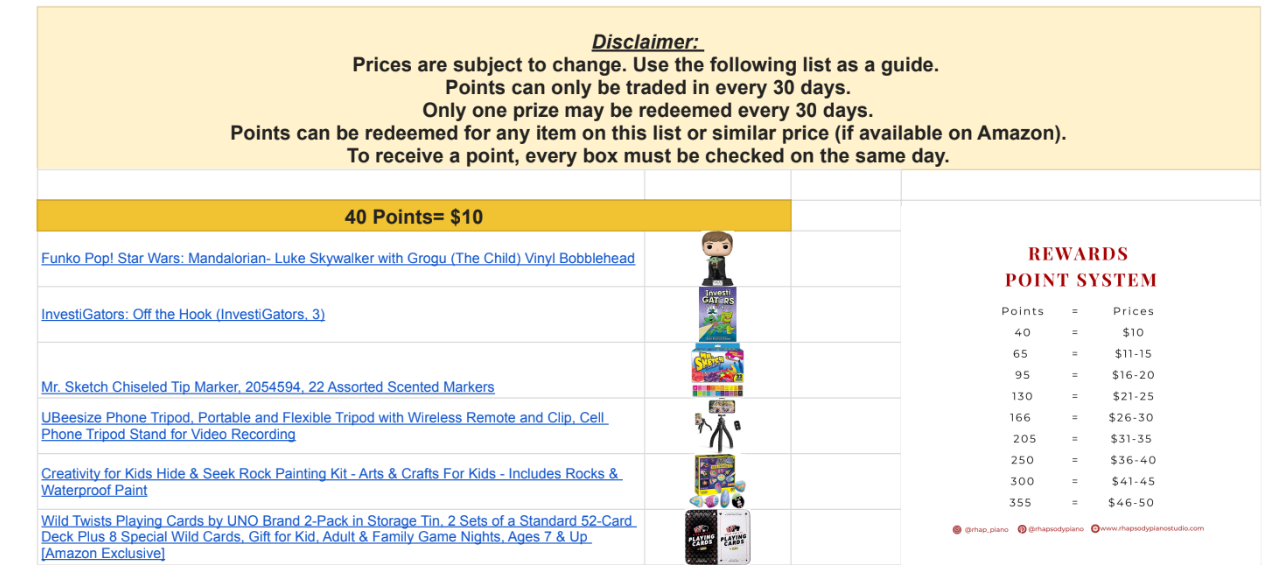

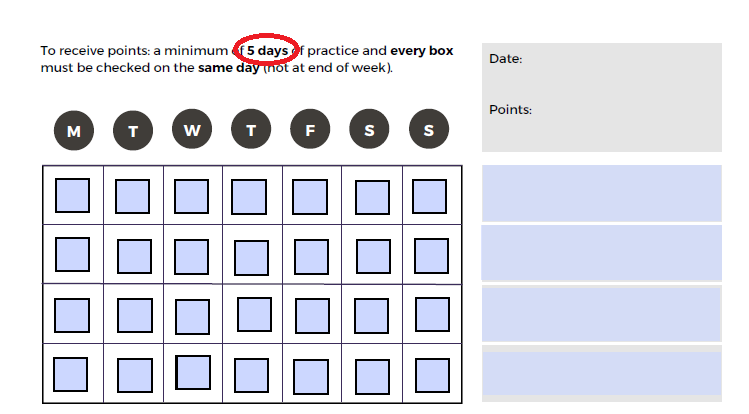

Let's look at these one by one. Reading and playing sheet music at a high level doesn't mean your rhythm will follow suit. It's because this is the wrong form of feedback. If you're studying a foreign language, you don't learn pronunciation by reading books. You won't improve because what you need is to hear someone - preferably native - speak the language. It's the same with writing, you improve by becoming a good reader. And to become a better pianist, you need to listen. This can only be done if you use the right resources: without an accurate model you'll have in-accurate results. For writers, these resources are books. For pianists, videos and recordings. If you're a beginner, I would suggest starting with videos - the added visual component makes things easier. Once you become more experienced, audio recordings are all you really need. Although, you still want to watch performances - if you want to improve your technique. Next, why is an accountability system important? Because even if you have all the right tools and resources, it doesn't matter if you keep forgetting to use them. Don't underestimate this problem: because the modern world is a giant distraction machine, without reminders to help you practice you'll get pulled apart in different directions without even noticing it. Ever tell yourself you'll watch just one YouTube video? Two hours later, you find yourself questioning your life decisions. This was a big problem for my students ... until I created a personalized practice journal with a checklist. But this was just half of the formula, I realized they needed a reward system on top of it. Some people might say all you need is discipline and while I also believe that work is the reward itself, nobody does anything for nothing. We need positive - and negative - reinforcements to keep us on track. The carrot and the stick. How do I emphasize this in piano lessons? Students get points for completing their practice for the week - by checking off their "tasks."

By the way, you need a reward system that's enticing enough for students to want to practice. Luckily, Amazon exists.

Of course, not every student cares. And after a while the practice becomes more satisfying than the actual prizes.

But what about negative reinforcement? Look closer ...

If they don't follow through on their instructions, they receive zero points for the week.

And I always frame it as a loss - we're inherently motivated to avoid pain rather than pursue pleasure. Lastly, your rhythm needs to be accurately measured. To do that you need the proper tool: a metronome. Why is measurement so important? Well ... would you hire a carpenter who doesn't use a ruler? The same principle applies with productivity - if you don't track your time then you have no idea how much of it you're wasting. But knowing this isn't enough, the biggest challenge I face as a teacher is getting my students to use the metronome regularly. Part of it is that they're not adhering to their accountability system, but it's mainly because of ego.

I hear these complaints all the time, but I know where they're coming from - I never used a metronome ... even as a college music major. It's one of my biggest regrets, I can't help but wonder how much better I would have played - and how much time I would have saved. But like I always tell my students, "doing the right thing is supposed to feel hard." You don't want to use a metronome for the same reason you don't step on the scale - the truth hurts. And it's definitely going to hurt if you've never used a metronome before, I guarantee you're going to crash and burn on your first attempt. To add insult to injury, it's like every tick of the metronome is telling you, "you suck, you suck, you suck ... " Even worse when the tempo is à la presto. And no matter how much you tell yourself that failure is part of the process, it's not like you look forward to it. So I suggest zooming out, realize that it comes down to gaining experience - a whole lot of it. The more you use a tool the better you get at it. And don't wish the metronome was easier to use - if you wanted to paint, you wouldn't blame the brush. Stick with it, if you're patient you'll eventually see results. And buck up, I have many tips for you on the way to make the process as easy and painless as possible. Here's some motivation for you: after using a metronome becomes second nature, it will actually make your practice a whole lot easier. When you're not over-fixated on rhythm, your mind will be free to focus on other elements of music (dynamics, articulation, etc.) which will add a whole level of expression to your playing. But before you get to this point your brain will fight you tooth and nail. This is because of concentration (lack of it). Learning anything unusual - a metronome is as unnatural as it gets - will sap your attention, fast. My suggestion? Think of it like going to the gym, if you've never worked out in your entire life then you're going to be pretty damn sore after your first day. But keep at it, your (mental) muscles will strengthen over time. And after all this, if you still don't feel the need to use a metronome, ask yourself: what's more important, your feelings or actual results? The tape doesn't lie.  Tools

Besides videos and recordings, an accountability system and metronome, what else do you need?

The rhythm app I recommend is Rhythm Sight Reading Trainer

What makes this app great is you have over 200 exercises to choose from. This means you're exposed to a variety of patterns at different levels of difficulty.

And it's fun. You also get instant feedback - a foolproof way to gauge your accuracy. And since the app is purely a rhythm game, all you need is one finger to tap with. Flashcards are a great way to supplement your rhythm practice. The strategies I'll mention later are active - think of flashcards as passive learning, they help you identify note values faster. When you use sheet music, it's not enough to just feel the beat. Many of my students have difficulty recognizing the type of note (quarter, half, etc.) while they're playing. So just like a rhythm app helps you isolate the physical sense, flashcards help with the visual aspect. Using a rhythm app and flashcards helps you shorten the learning curve with sheet music. You can also use these two tools with interleaving, which I'll talk about when we get to strategies. The One Thing

Now before we learn some strategies, let's first talk about the "master" skill you need to ... umm ... master.

This skill is subdivision. Once you fully comprehend this concept, there won't be a rhythm you can't handle.

To help illustrate, imagine you have a square. You divide this square into smaller squares.

Then, divide it again.

Let's do it one more time.

This is the essence of subdividing rhythm.

To further explain, subdividing helps you understand rhythm on different levels. It's like taking apart a machine and putting it back together - you know it inside out. Another example is what I had to do in grade school: dissect a frog (thankfully I didn't have to go Frankenstein and put it back together). Subdivision is also a version of varied practice: practicing one thing many different ways, rather than doing it the same way over and over again. Let's see how this helps you count better when it comes to sheet music.  Sheet Music

In sheet music, longer notes are the ones you'll have the most difficulty counting - it's definitely what my students struggle with.

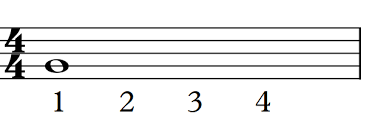

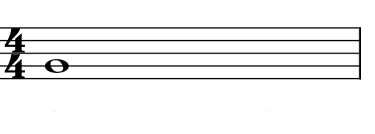

Quarter notes are the easiest to count since they fall on each beat of a 4/4 time signature.

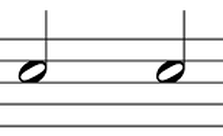

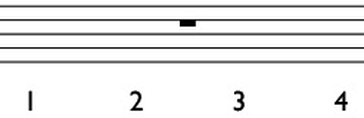

But when you see a half note, you have to visually imagine, or feel, the beats in between.

It's hard enough with a half note - with a whole note you have to keep track of the next three beats.

So when my student sees a whole note, they erroneously move onto the next measure because there aren't extra notes to help them track each beat.

Practicing subdivision solves this problem: you'll be able to sense the pulse of an entiremeasure.

This also helps with rests: many students tend to think of them as when the music stops. Remember, this is wrong - treat rests like silent notes.

Next, let's dive into 2 effective practice methods.

Method #1

The first tactic involves a scale.

Important note: make sure you use a metronome at all times. Play one octave (up and down) counting 4 beats for every key you play (whole note). Repeat the octave, this time counting 2 beats per key (half note). Continue this process with quarter notes (1 beat), eighth notes - this time playing 2 keys per beat - and even sixteenth notes (4 keys per beat). You can also reverse the order (in fact, I recommend it):

This idea is a simple and versatile method to master any odd rhythm you come across (5 notes, 7 notes per beat), while simultaneously increasing your range of motion (several octaves). Method #2

Now back to sheet music: we'll use the same tactic, but the difference is changing the beats per measure.

For a 4/4 time signature, set each quarter note at a BPM of 120 - count 4 beats per measure. Then, switch it to 60 BPM - this time counting 2 beats per measure. Lastly, up the challenge even more by changing it to 30 BPM - 1 beat per measure. The challenge is to keep the correct timing of notes per measure while maintaining the tempo (speed) at a consistent rate each time you change the pulse (4 beats, 2, 1). With these 2 methods, your rhythm issues will be a problem of the past, but don't expect overnight results: precision is a master skill. Look up a YouTube video of Marco Pierre White (master chef) chopping an onion - he chops it so finely the vegetable literally dissolves. More evidence: in masterpieces of historical art, what stands out is the insane amount of detail - read Leonard Da Vinci's biography sometime. It's the same with a great novel: so many attuned specifics it feels like you're living the story you're reading.

Up next, strategies.

Simplify

A philosophy I've adopted when teaching students a concept for the first time is to make it as easy as possible - this means teaching rhythm is last on my list (IMO the most difficult skill to learn).

So we focus on other things: note reading, sheet music, and proper playing mechanics. In my experience, having these skills down-pat makes rhythm more palatable. But I've definitely come across the opposite scenario: students that have great rhythm - and are also great at playing by ear. The flip-side: they can hardly read a note. Anyways, once we get around to making rhythm the goal, we either use music they've already completed or brand new material at an easier level.

When the music is already familiar - or simple to play - there's less for them to think about (more concentration).

A similar approach is to practice rhythm with songs or music you already know by heart. For instance, I've never had a student struggle to play "Happy Birthday" on beat. And not surprisingly, they pick up "Hedwig's Theme" fairly quickly. Easier music also provides a way for you to benchmark your progress. A useful question to ask yourself is, which of my piano skills needs work? The notes might be easy to play, while you're having a hard time keeping the beat. Or you might be keeping the beat perfectly while missing note after note. It's a simple, easy way to detect weaknesses and make the proper adjustments. This is why the Faber Studio Collection is my weapon of choice: an abundance of songs you'll already be familiar with. As a side note, I never recommend any beginning student learn piano with classical music - it's a very difficult genre to grasp if you're unfamiliar with it. By the way, you can also opt to not play your piano music (not saying you should quit). Instead of pressing the keys, you can just clap - or verbalize - the correct rhythm while following along with the sheet music. To improve accuracy, I recommend playing the audio track or video while you do this. It's another way to isolate the rhythm - similar to picking the easiest sheet music to practice. Oh, and a bonus benefit is your visual tracking gets better.  Powerlaws

Another strategy I recommend: the 80/20 rule - it's keeping in lines with making introduction of new materials and challenges as easy as possible.

Here's the only math you need to know: spend 20% of your time on practicing rhythm, 80% on whatever else you want (sheet music, technique, ear training, etc.). This makes using a metronome effortless. I mentioned earlier that students are stubbornly resistant to this tool, and without the 80/20 rule they tend to get overwhelmed. In the past, I used to tell students to use a metronome 100% of the time. But all it did was deflate them. Now, I realize how unrealistic my expectations were. So when they hear they only need to spend 20% of their time with a metronome, the reaction is instant relief. Once they get the hang of it, we don't stop there: we reverse the ratio - 80% of their time with the metronome. But remember to do this each time you level up - when you work on more challenging music (20% with, 80% without). Rinse, repeat. The 80/20 rule works well because of the added constraint, or limit. This is why we need deadlines to finish projects or why I always work using the pomodoro technique. This is thinking inside the box to create results. Interleaving

This last strategy is one I'm betting will become your favorite: interleaving.

Out of all the strategies I've shared with you today, this one will speed up transfer the most. Interleaving is practicing related but distinctly different activities. If you were an athlete you could play soccer, baseball and basketball (all related but different). For you football buffs I have one prime example: Patrick Mahomes. Back to piano. ​In one session, here's what you could practice:

Don't forget about the previously mentioned methods:

As an aside, there are other concepts such as small-chunking, varied practice and spaced repetition I haven't gone into. I'm not going to mention them here because I've already covered them in this blog post. You'll want to read that article after you're done today: when you use what you learn there, your results will be supercharged. Coda

So I hope you enjoyed today's brain dump on rhythm.

I know it's a lot to take in, but what I strive to do with most of my articles is to teach you principles - so you don't need someone to give you the answers. If you've read my blog posts on reading music notes and sheet music, you'll notice that the process is similar - if not the same.

If it's your first time thinking this way, realize you can apply the principles I've shown you on this blog to learn anything you want in life.

Just understand that any time you learn something new it's going to suck. So when learning gets tough (it's inevitable), remember the Navy Seal motto: Embrace the Suck. Things don't get easier, you just get better. Lastly, remember that accurate rhythm is just a means to an end. The goal isn't to be a musical robot, it's to express yourself as much as possible. Go ahead. Get rough around the edges ... and lost in the music. Even if you wander too far, you'll always find a way back. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

This article contains affiliate links... If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

Note: Make sure you also read the last post after today's article, apply what you learn in both articles together.

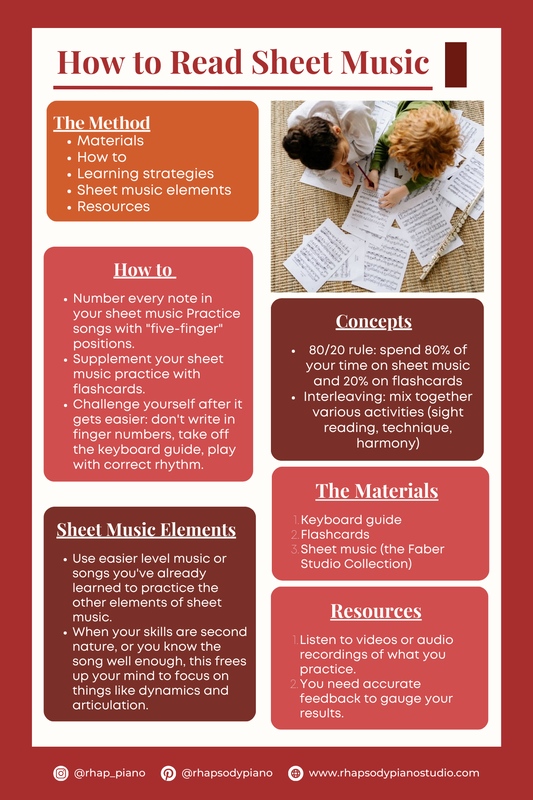

I've heard a lot of things throughout the years about sheet music, mainly from misinformed subscribers on my YouTube channel. "Reading sheet music is too hard, it's impossible to learn by yourself." Yet reading sheet music is a skill anyone can learn, you don't have to be born with it. There's no secret, just a better way. "Whatever. You just need to play by ear." Don't get me wrong, playing by ear is a valuable skill - I'm trying to get better at this too - but it's not meant to replace sheet music. It's supposed to be an additional ability to stack onto the skills you already have. "But playing by ear is so much easier than reading sheet music." This isn't true either. Think about it, you can begin playing immediately with sheet music, whereas when you play by ear you have to recreate everything you hear. Sounds way harder to me. There's also more guesswork involved with listening, whereas sheet music that's professionally, and faithfully, transcribed is 100% accurate. Besides, what do you call a person who can't read? ILLITERATE. Why put yourself at a disadvantage? I'm not going to sugarcoat it: learning to read sheet music is hard. But with preparation and understanding, it's completely within your reach. So here's a rundown of what you'll learn in this article:

For simplicity's sake, I'll not only refer to sheet music as both reading and playing, but also at its most basic sense: a rudimentary level of note reading.

For now, forget about time and key signatures, dynamics, symbols, phrasing and everything else.

Theory comes later. After reading today's article, you'll understand this has more to do with lack of understanding about the true process of reading sheet music - and the proper mindset to get there. It's a long road to reading sheet music and the worst thing you can do is expect short-term results. For a while, you're going to feel like a fish out of water. But if you dedicate yourself to the longterm, I promise you'll see results. Just keep going and you'll reach that one, sweet day where everything clicks for you.  How to Read Sheet MusicWhy People Avoid Sheet Music

Before we get into why sheet music is so friggin' challenging, and what to do about it, let's talk about why piano players avoid sheet music in the first place.

I believe it boils down to 2 things:

Misbelief

The reason we're brainwashed into thinking we need theory to learn piano has to due with our school conditioning.

Because what matters in school? Grades, just grades. And if you're not up to par? They batter you with homework assignments. So we naturally grow up thinking we need an instruction manual, a set of problems to solve with pen and paper, for everything we learn in life. No wonder we apply this standard to sheet music. You might be wondering what the problem with that is - it's because there's no equation for reading sheet music. It's is a hands-on process, there's no magic formula. You gain this skill through intuition, experience. And this presents problems ... because there's no clear roadmap with a trial-and-error approach. So the typical music teacher defaults to drowning you with theory. They do this because theory is like homework, it has clearly defined criteria: just do your problems and correct your answers. It's all they know how to do - they don't have their own unique method. The other reason is that it eliminates uncertainty. But this is a huge error: uncertainty is inherent in the learning process. You can't solve every problem you come across by knowing everything in advance - it's like trying to ride a bike by studying statistics. Realize that theory comes after action, not before it. Studying too much of it too soon will harm you more than help you. All you need is a simple approach and hands-on practice. This requires a leap of faith, so expect to get your hands dirty. The more mistakes you make, the better. It's about taking so much action that you don't even have time to think or (over)analyze what you're doing.

Fire! Ready, aim ...

Excuse-Making

Letting go of previously held beliefs is hard enough, but what's more difficult is not getting in your own way.

I'm not saying that you're your own worst enemy, it's that our brains are wired to keep us out of trouble - and sometimes it makes us avoid what's good for us. For example, we're equipped with ancient software for modern times. So whenever we come across something mentally strenuous, we unconsciously see that as a danger and do whatever we can to avoid it. I remember trying to read a book for the first time, about halfway through the first page I started to doze off - I didn't think, wow I need more concentration. I thought, man this is so boring. And this is why most piano players gravitate to learning by ear - it's simple. Monkey see, monkey do. Not that there's a problem with that, it checks the dots: intuition hands-on The problem is when you start telling yourself you don't need to learn sheet music. Part of this is because of what we mentioned earlier, educators treating it like mathematics when it's more like experimentation. Trying to stick a square peg into a round hole. But it has more to do with ego: if you've reached an intermediate or higher level, the last thing you want to do is start over - which is what learning sheet music feels like. Yet that's exactly what it is, it's learning a brand new skill. Being good at soccer doesn't make you good at basketball. Yes, they're both sports but both require different skillsets and abilities. Instead of realizing this, the misguided piano aficionado would rather salvage his pride. Now, if you don't want to learn sheet music that's totally fine by me: just don't lie to yourself. Is it that you can't do it or that you won't even try? Hmmmmm? I really hope you understand that it's the latter. Look, no one wants to start from zero and no one wants to admit they're wrong. But there's no shortcut to the process. Learning necessitates mental effort, and sometimes (many times) you experience frustration. This isn't exactly super motivating, but who cares? What's good for you isn't always enjoyable. Broccoli is better for your health, but we'd rather chomp down on a double cheeseburger. Giving into these short-term temptations is what ruins us for the long-term. So my version of "vegetables" might be contemporary music. I loathe most of this genre, and much of what I hear I don't even consider real music. Yet I still practice it ... because it helps me become a better pianist. But some good news, later in this article I'll show you the method I've perfected and field-tested on my students over the years. You don't have to figure it all out by yourself, once you understand all the main points you'll know what you're getting yourself into.

After that, you just need a solid plan to follow through on.

What Makes Sheet Music Hard

There are 3 things that make sheet music challenging:

Visual Tracking

From my experience teaching students, the most difficult part of sheet music is tracking visually with your eyes - keeping your place on the music score at all times.

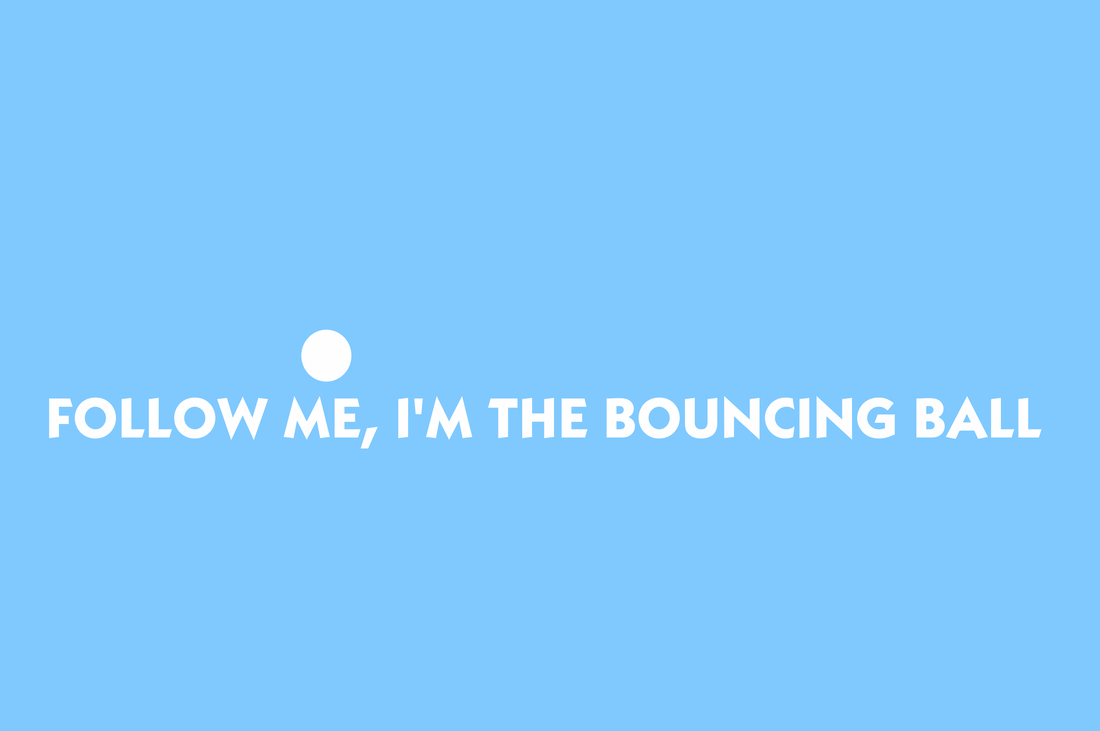

Ever watch Sesame Street? If so, you might remember those bouncing dots that helped you sing along with each song.

So if we needed that much help with words, imagine how much more challenging it is when it comes to notes on a page.

This doesn't apply to just students or amateurs, here's an embarrassing personal vignette: I once turned pages for my wife, and a colleague, during a concert. She was performing a "four-hands" piano duet (2 people on one piano). I actually thought I was following along quite well until ... my wife started whispering to me during the actual performance. I had no idea what was going on ... until both pianists came to a dead stop. Her partner awkwardly took his right hand off of the piano and turned the page himself. Not a fun time, but I'm glad it happened - it's easier to teach people to overcome struggle when you've gone through it yourself. And no matter what you hear, music is not a universal language. You don't read music like you read a book. It's because we communicate linguistically, reading music is more like coding a program. It's similar to learning a language that isn't close to your native tongue - imagine learning Arabic or Chinese as an English speaker. Some advice: don't obsess about note-reading so much that you miss the forest for the trees. When you get to a higher level, you're not going to see individual notes anyways - you notice patterns. So ... how do I help my students with this process?

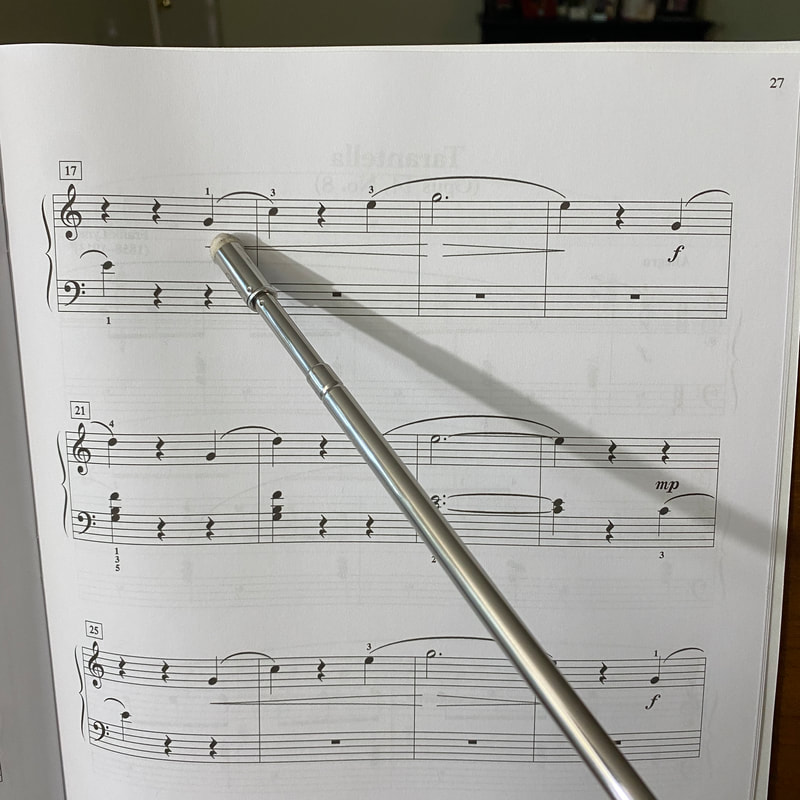

It's ridiculously simple: I use a physical, extendable pointer.

And I guarantee you that most teachers won't even consider this method - they usually believe complex problems require complex solutions.

But you know better, so here's how to do this at home - and you don't even need a piano. Listen to a recording of your music and follow each note, or musical line, using your finger as a guide. That's it. A good question you might have is how long do I have to do this? We'll answer this in the section on concepts. Sensory Overload

What compounds the difficulty of visual tracking is that there's a LOT to pay attention to (besides notes):

So when a beginning student sees this for the first time:

I know it looks more like this:

And this is just information on the page, what about all the senses involved with piano playing?

This is just with a single line of music, imagine how much more complicated things get when more notes are added in different pattern. You can't do everything at the same time.

Yet most teachers and coaches will make you do this, and yell at you for "not trying."

Instead, the solution is to simplify the process so you can focus on one single thing at a time.

It's not that there's anything wrong with doing everything at once - it's just a longer, and much more frustrating, process. I think the better option is to do less in order to get some quick wins - this way it's easier to build long-term motivation. So start with the smallest amount of information you can manage, and then gradually add a layer at a time. Here's what the basic progression looks like:

When you practice these separately, it proceduralizes more quickly (more on this later). No Clear Timetable

The last reason why sheet music is hard to learn is that it's not a linear process - you don't just consistently level up.

It's why working out is easier than eating healthy - the results are more visible (no one thinks you got that six-pack by eating broccoli). In any case, it's the element of randomness and uncertainty that makes people give up too soon - this lack of a clear deadline is why so many people can't stick to sheet music practice. This is because learning sheet music is like developing a habit - with any habit, you can't predict when it will stick. It's something that's learned rather than taught - I can do my best to guide each student at their lesson, but sooner or later they realize I can't do it for them. So realize the journey is different for everyone: some will pick it up in a few months while others take much longer. Don't focus on results. Instead, make the goal how much time you spend. You can dictate how much (high-quality) effort you put into the process, you can't control the outcome. Pro Tip

Now, it's not all doom and gloom. In the next section we'll discuss concepts that will illuminate the road ahead of you.

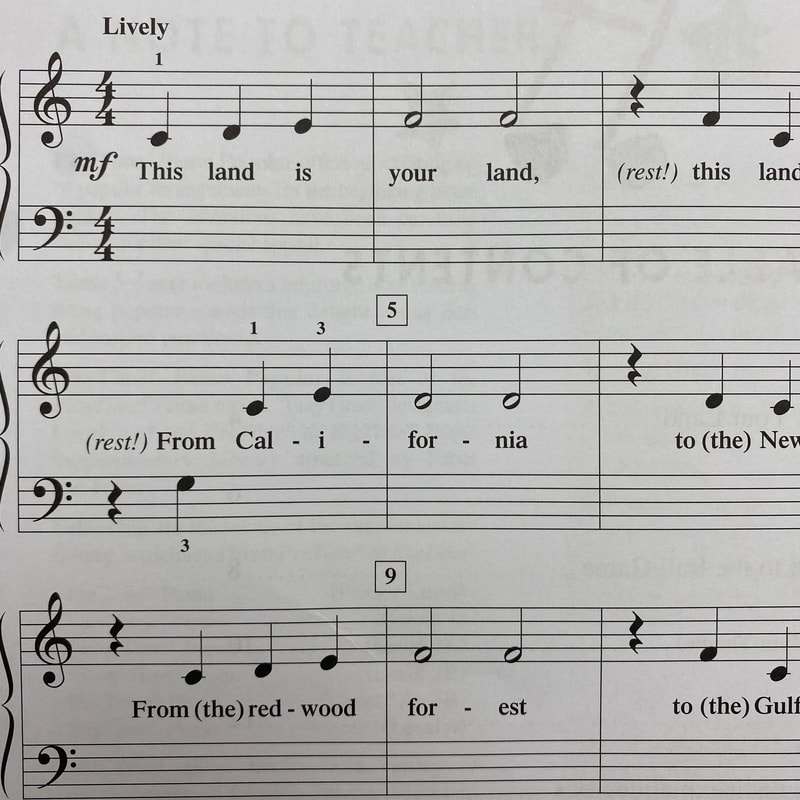

First, a valuable tip: start with music you already know (preferably by heart). If you practice with songs you're familiar with, then you already understand the form, structure, melody and cadence (rhythm) - at least on a subconscious level. This familiarity is what will speed up the learning process for you, since you have less to think about. Instead of a blank sheet, it's like having a blueprint to work from.

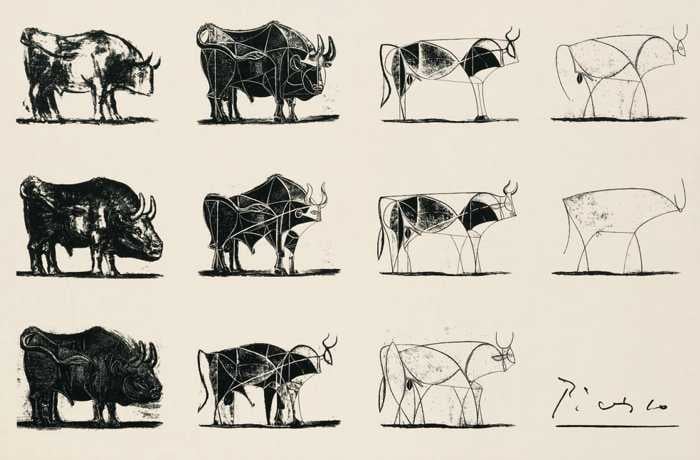

Picasso's Bull

The less you have to think about, the more action you'll take.

The more action you take, the more progress you make.  Concepts

Here are 4 concepts that will enhance your understanding of the sheet music process:

Transfer is how long it takes for one field of learning (related or not) to show results in another. If you're studying a language, this is when you're able to use all the vocabulary - previously memorized - in a real life conversation. This is why you supplement your sheet music practice with flashcards - individual notes. It's also why most of what we learn in school is useless for real life - it doesn't transfer. Proceduralization, from Scott Young's book Ultralearning, is when a skill becomes autopilot - like tying your shoes.]

Because there are many different pieces that need to lock in place, this is why sheet music takes so long to get good at - and also why it's better to do one thing at a time.

Here's how the process typically looks:

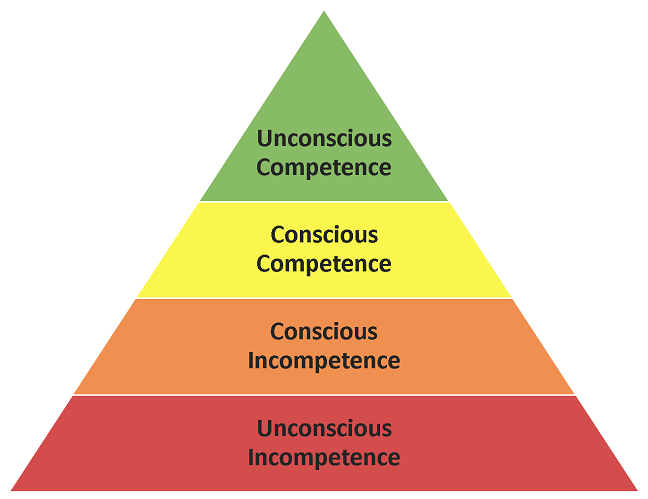

This is why it's not such a great idea to do everything at once - it will take forever for each skill to lock in. Now, if you've ever wondered why you have great days, bad days, and all sorts of days in between, I present to you The Levels of Competence.

This is why learning can feel frustrating: each time you evolve to a higher level it feels like starting over. As a beginner, you work hard to get to the intermediate stage - only to have to learn a new set of skills or wait for current skills to consolidate. But don't bemoan this fact, accept it as part of the learning process. Will there be a moment when this ends? Probably when you get to the concert pianist level - the highest level repertoire you can study. Until you get to this point, you'll frequently struggle with your material because you're discovering new, unfamiliar patterns for the first time. So when you learn these patterns, and continually learn new ones, you gain experience. Pattern recognition is what leads to expertise. This is why concert pianists seemingly learn repertoire 10x faster than us mortals, there's hardly a pattern they haven't seen before. Lastly, there's what James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, calls the plateau of latent potential. It's when you feel like you're stuck, making zero progress. In reality, you might be close to a breakthrough. This is why you should expect plenty of ups and downs, progression and regression. As mentioned earlier, it's not a gradual climb: it's more like a rollercoaster ride. Be patient and play for the long-game. Don't give up too soon, you might be one inch away from pay dirt!

But do exercise caution and notice when you really are stuck. If (when) that happens, refer back to these 4 concepts - they'll clue you in on how best to adjust your course of action.

Next, the action plan. MethodMaterials

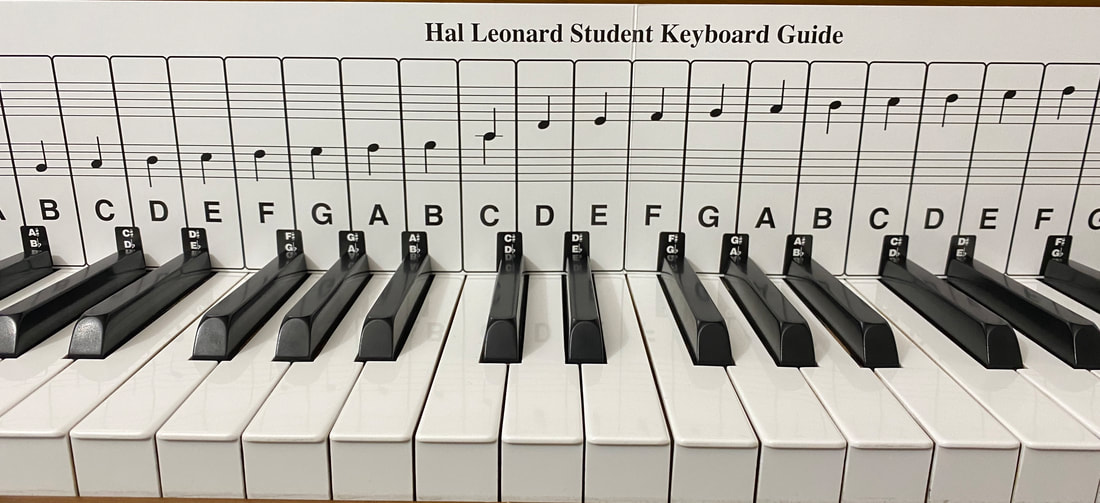

Before you learn the method, you need the right materials.

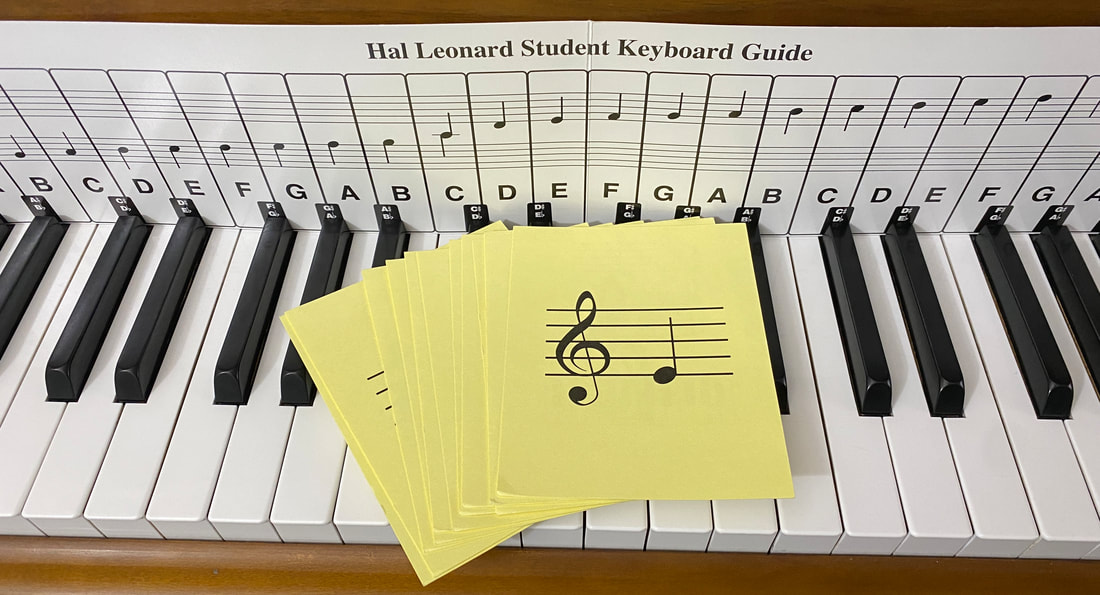

A keyboard guide helps you locate and identify notes. For the immediate future, leave this on your piano or keyboard at all times. Supplement your sheet music practice with flashcards. Due to transfer, quizzing yourself on individual notes will help your overall sheet music reading ability. If you still haven't checked out the last blog post, read it now to learn my process.

Lastly, grab a book from Faber Studio Collection. Visit this page to learn about the benefits and pick up my free guide (a curated list of the entire collection).

Since you can listen to the material before you purchase, you'll be able to decide which level is most appropriate - I recommend beginners start at the "pretime" or "playtime" level. This collection is the foundation of my piano lessons, I've taught this to my students for over a decade - once you get your copy, you'll see why. You'll also find a huge selection of music you're intimately familiar with, a great way to take advantage of my earlier tip on choosing music you already know. Procedure

Now, the method.

Here's how I define the basic stages of learning sheet music:

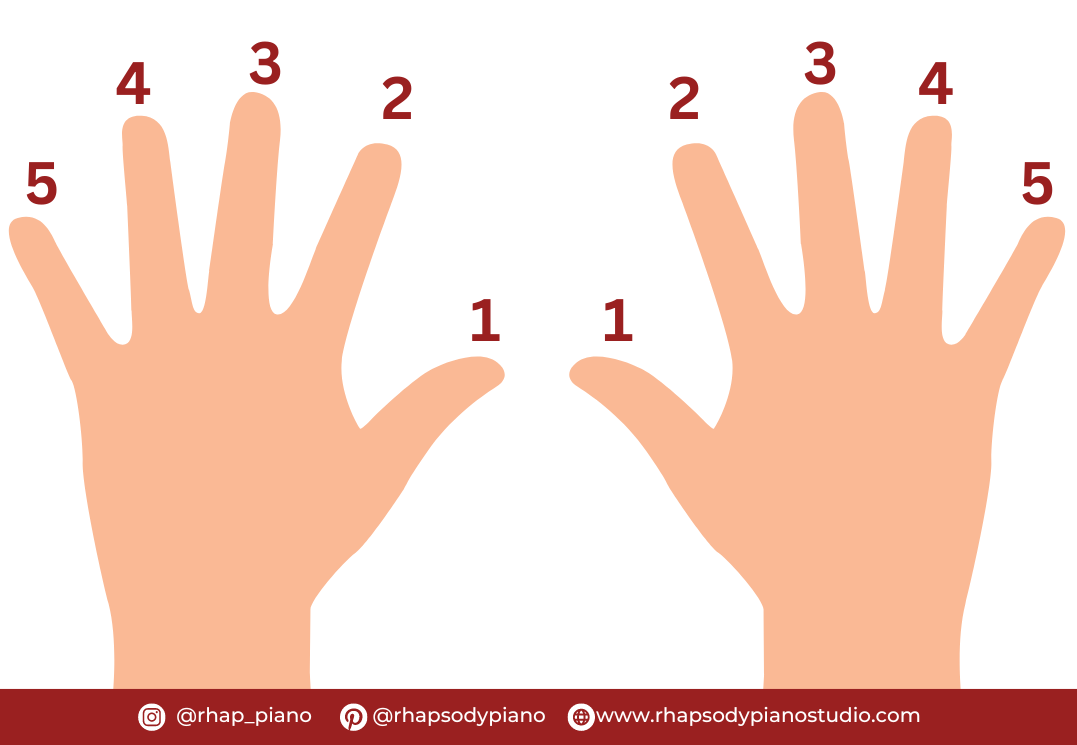

On your sheet music, place a number above - and below - every single note. Read this blog post to see how to do this.

Each number represents a finger, so at this stage you'll only concentrate on playing each note with the correct finger. For this reason, start with easy enough music that only contains "five-finger" positions. Since you won't have to move your hands this means more action - and faster progress. And you don't have to consciously identify each note letter. As long as you continue to supplement your practice with flashcards, you'll learn them at a subconscious level. When things get easier, mix up your practice by:

But it's not do or die, you can go back to finger numbers or use the keyboard guide any time you want. In fact, expect turbulence. Once you get the basics down (unconscious competence), you'll begin to recognize patterns. And when you get better at pattern recognition, the next step is to learn form and structure. But this is a high level skill - many years down the road. If you get to this point, you can pick up a book on musical form or study theory. 80/20

Don't try to spend equal amounts of time on everything, unless you want to make progress at a snail's pace. Instead, use the 80/20 rule: spend 80% of your time on flashcards and 20% of your time on sheet music.

You can also flip it around, 80% on sheet music and 20% on flashcards. Experiment to see which formula gives you the best results. Once you improve, there will be more options: you can use the 80/20 rule in different ways. At the intermediate level, you can spend 80% of your time on current level repertoire and 20% of your time on easier sheet music. Practice easier music so you can continue to learn more patterns. Challenging repertoire might be good for your technique, but not your reading ability - in essence, you're practicing the same pattern over and over again (nothing new). It's also more motivating since it allows you to fortify your reading skill without having to give up your current musical projects.

Have your cake and eat it too.

Interleaving

Interleaving is another strategy to enhance the quality of your practice sessions - and it's more fun than the traditional course of action.

Instead of doing the same thing repeatedly, you mix together various activities, skills, projects, etc. I use interleaving to get the most out of my favorite pastime - reading. I have 3 or more books in my rotation at all times and whenever I get bored or lose focus, I immediately switch to a different book. This is how I'm able to effortlessly read for hours on end - only taking a break if I so desire. How to apply this in practice? If you're new to piano, purchase several books at the beginner level. When your attention wanes or you hit a wall, jump to another song or book (flashcards are always in play too). It's like taking a break from practice - by practicing something else. And due to spaced repetition you don't have to stick with a problem for long: good enough is good enough. If you're at a higher level, practice a variety of genres and easier music. Mix in other diversions like sight-reading, technique or harmony (more on this in the next section). Some Last Tips

You might be wondering, what about the other elements of music? What about dynamics, articulation and phrasing?

Solution: practice these concepts at an easier level. How easy? The basics should be on autopilot. This frees up your mental resources to purely concentrate on these other aspects. If you want to speed up this process, do this with music you've already completed (similar to the pro tip I mentioned before). It's like watching a movie twice, you notice more details you weren't aware of the first time around. Also, regularly refer to videos or audio recordings. This is because you need a form of feedback, and these resources are the most accurate ones available. Additionally, use these resources as benchmarks, so you can see how far away, or close, you are to your goals. On YouTube, there are useful features such as slowing down the playback speed and pinch-and-zoom (zooming in on the screen.) Lastly, don't forget about the Levels of Competence. Remember that you'll go through these stages over and over again as you improve. Don't fret: it feels like you're getting worse, when you're just adapting to the next level of difficulty - overcoming the plateau of latent potential.  Additional Strategies

Now, some additional strategies:

This trifecta helps by exposing you to more patterns on a visual (sight reading), physical (technique) and auditory (harmony) level. Sight Reading

Why is sight-reading useful? Since most examples are short, you can get through quite a few in a short amount of time.

This shrinks the feedback loop, which quickens your progress. When you first start out, you'll definitely make a lot of mistakes.

But keep at it - continue supplementing your sessions with flashcards and you'll get more accurate over time.

Technique

You'll practice technique: scales, arpeggios and chords. Bonus points if you do them in as many keys as possible.

These 3 exercises represent the most fundamental patterns in all of music. It's like having a blueprint for any sheet music you come across. But it's not just about how fast you can play ... Harmony

... a pianist is only as good as their ears.

To hone your listening ability, work on harmony - chord progressions, transposition or solfege. And listen to as much music as possible, it's a great way to enrich your musical vocabulary. Buena Suerte

If you had any misgivings about sheet music before, I hope this article gives you the confidence to tackle this challenge.

I'm confident what you learned today will work for you. After all, it's a process that I've repeatedly used to help my own students succeed over many years. Remember that sheet music is best learned like most skills: through hands-on practice. Learn through personal experience, not through textbooks. You don't need a perfect formula, you just need a daily commitment: discipline. You'll get it done as long as you want to. Trust yourself and review this post from time to time, since repetition is what leads to mastery.

I wish you much success.

Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

This article contains affiliate links. If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

In the next article we'll get you up to speed on reading and playing sheet music.

One of the most common questions I get from clients is, "do you teach students to read notes?" My answer is always yes - though in my head I'm thinking of course, why on Earth would I not be able to teach this elementary, basic skill?

It wasn't until I had transfer students here and there that it started to make sense: most of them could barely read music. Even more shocking - a few had been taking lessons for years. What gives? How To Read Piano NotesThe Piano Note Reading Myth

It has to do with lecturing birds how to fly.

This is a concept from Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan. As an aside, he's such an important author that I regularly reread all his books at least once every year. Here's the idea in a nutshell:

Sounds ass-backwards, doesn't it? This is why people think education leads to wealth, when it's the exact opposite. It's also why people go to business school to learn how to start a business. Funny, my dad didn't even have a college degree when he opened his first dry cleaners. Anyways, back to our subject. It seems in the field of education, there's an unhealthy obsession with theory. This idea extends to music lessons as well. In college, I remember taking a pedagogy class - it was 90% theorizing and 10% actual hands-on teaching. BORING. Look ... you don't learn to cook by memorizing recipes. Another common question I get, "how much theory do they need to know to read notes?". Answer: NONE. The Right Way to Read Piano Notes

So if you want a simple approach that relies on zero experience, and zero theory, this is the article for you.

For over a decade I've been teaching students to read notes from their very first lesson, through action. And my success rate is 100% (humble brag). Here's the breakdown for the rest of this post. We'll cover the basics from the complete beginner level. I'll share the simple, affordable tools you can purchase from Amazon to replicate my approach at home. Then I'll show you how to use each tool and the step-by-step process I've developed to get you fluent in no time. Sound good to you? Then let's do this!  Basics

Here's the good news, there are only 7 letters of the entire musical alphabet:

A B C D E F G This is something every musician on the planet is familiar with (unless they don't read). Now, take a look at your instrument.

You'll notice 2 colors: white and black. Ivory and Ebony.

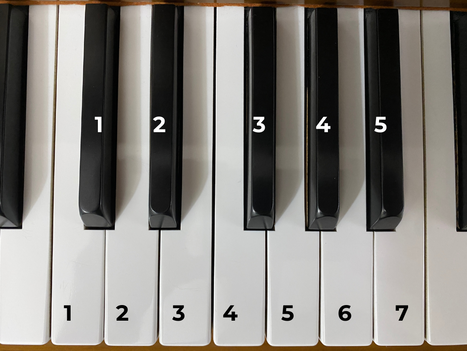

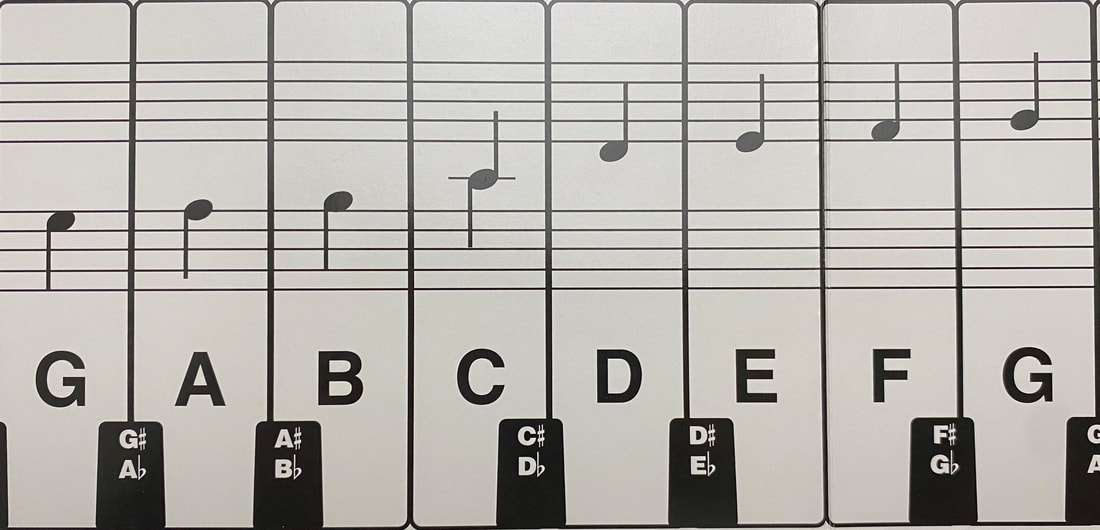

And the black keys are placed higher - don't ask me why. We use the black keys to identify each "letter" - a.k.a. white key. Here's the first pattern to familiarize yourself with.

And the next.

Here's how it looks all together.

Now, let's look at it again, this time with each white key labeled by letter.

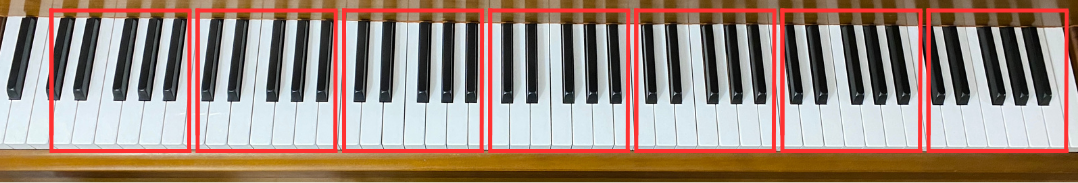

That's all there is to the layout on a piano, this cross section repeats itself up and down the keyboard.

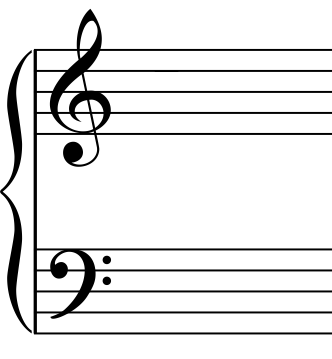

Next, the grand staff.

This is what we use to read actual music. But since we're focused on single notes, we're going to split the grand staff across the middle. Let's start with the upper half.

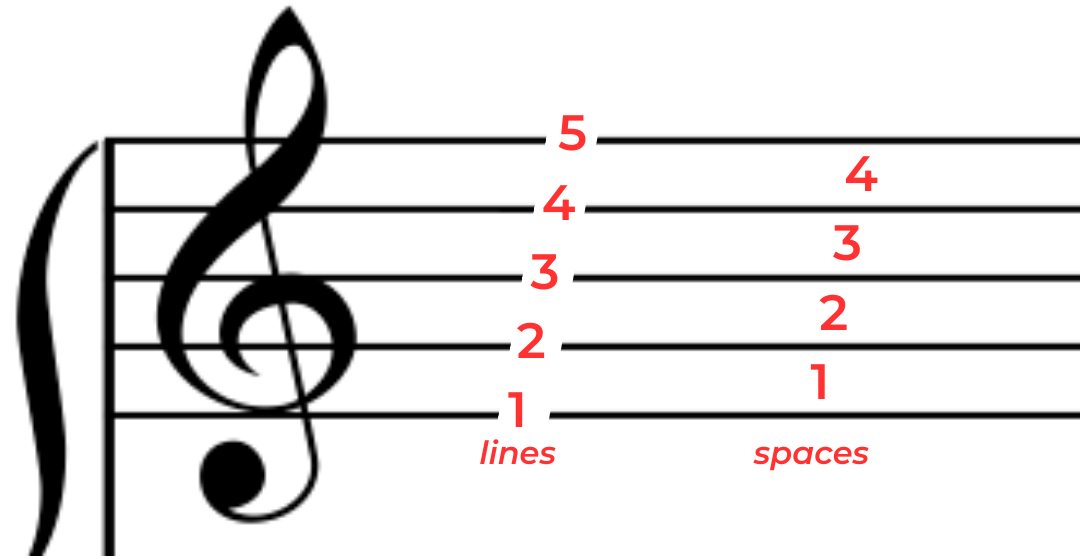

This is the treble clef. Basically, everything from the middle to higher range.

You'll notice 5 lines and 4 spaces.

Each line and space represents one of the letters of the musical alphabet.

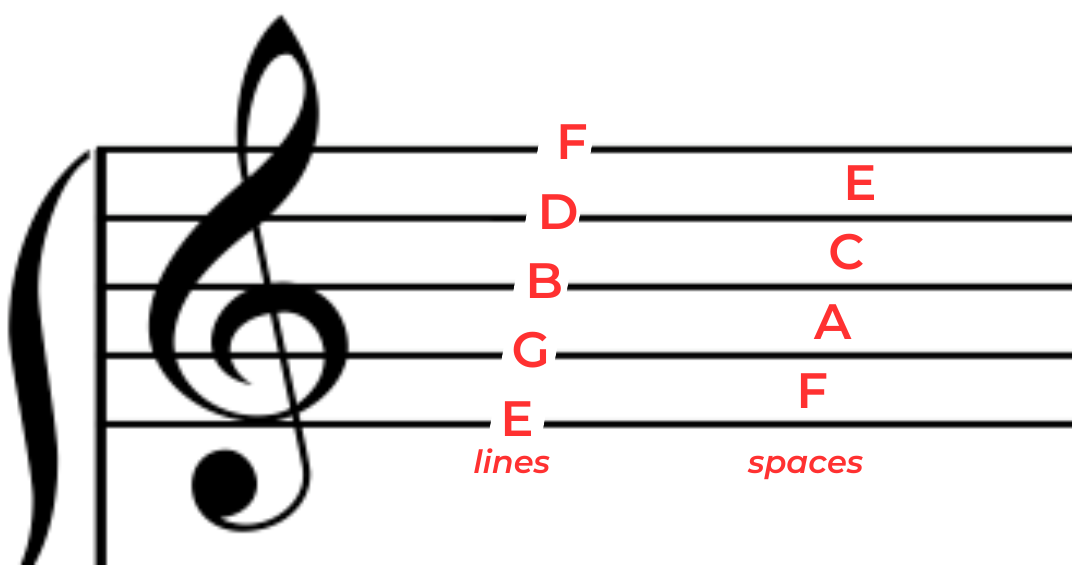

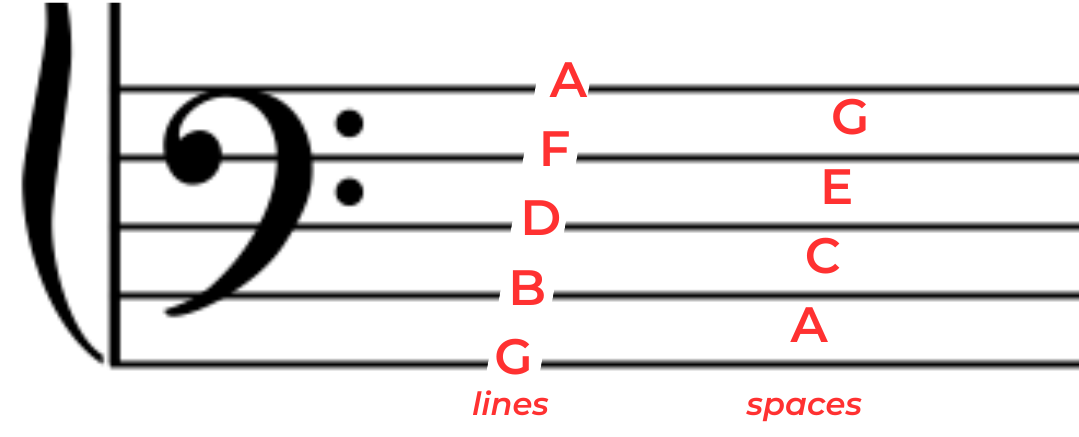

The same applies for the bass clef (middle range to lower).

If you were taking a traditional music lesson, this is where the teacher would have you learn a mnemonic. If you don't know what a mnemonic is, here are some examples:

Now, mnemonics are pretty useful: I use one to teach my students the order of sharps and flats. However ... when it comes to note reading, you do NOT want to learn any mnemonic of any kind. Period. You're actually worse off if you do. It's like taking a shortcut: short-term fixes usually come with long-term, negative consequences. The myth is that you must memorize the letter that each space or line represents. WRONG. Instead of memorizing letters, you just learn to recognize the location of each note on each line or space. In fact, I dare say memorizing letters is a byproduct of this process and not the main goal. By the way, we'll get you to do this subconsciously - see perceptual processing later in this article. In fact, I'm so adamant about not learning mnemonics, I'm not even going to mention this particular one for fear it will get permanently lodged inside your head. It's a double-edged sword: once memorized, it's nearly impossible to forget. When a student comes to me pre-loaded with one, we waste a lot of time trying to get them to unlearn it. It becomes a crutch. Instead of just playing the correct note, they cycle through the entire damn phrase. Over and over again. Thinking and thinking, but not playing. If you've never learned a mnemonic to read music, count yourself lucky. Unlearning is a difficult process, but doing it the right way from the start is easy - though it takes longer (as it should). But if you've already learned one of these dastardly expressions don't fret. Later in this post, I'll show you how to banish it from your memory.  Tools of the Trade

Here's all you need:

These materials are the foundation of my entire approach.

Let's start with the keyboard guide. It has two purposes:

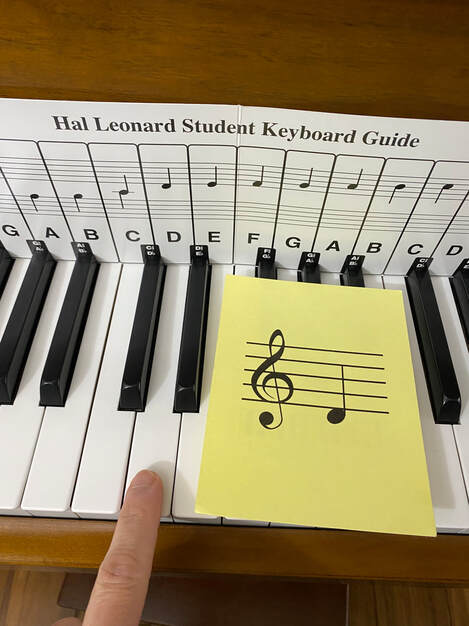

Set it up on your keyboard or piano and see for yourself:

This is how we completely bypass the need for theory: with the guide, it's simple to locate each note.

Side note: This guide fits my baby grand piano perfectly. If it doesn't fit snugly on your keyboard, you may have to make some adjustments - get those scissors out (snip, snip). Lastly, if you're new to the note-reading process, you're going to keep this guide on for quite a while. Now, just a short blurb about flashcards. If you prefer digital (free), then just download an app - there are probably hundreds to choose from (good luck). Me? I prefer a physical copy, it's more versatile (you'll see why).

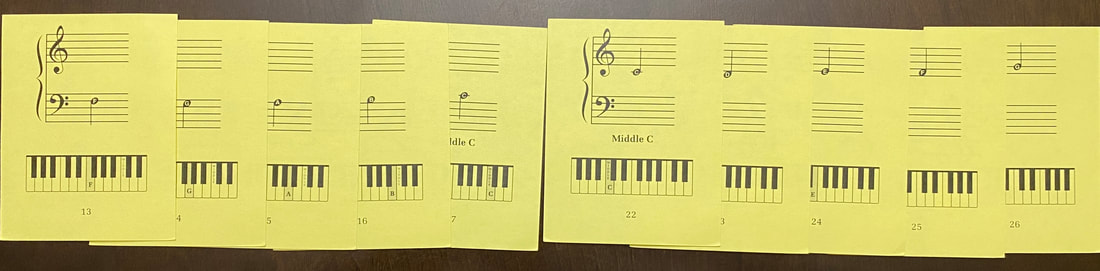

In the next section you'll use flashcards to physically locate the correct keys via the keyboard guide.

The Method

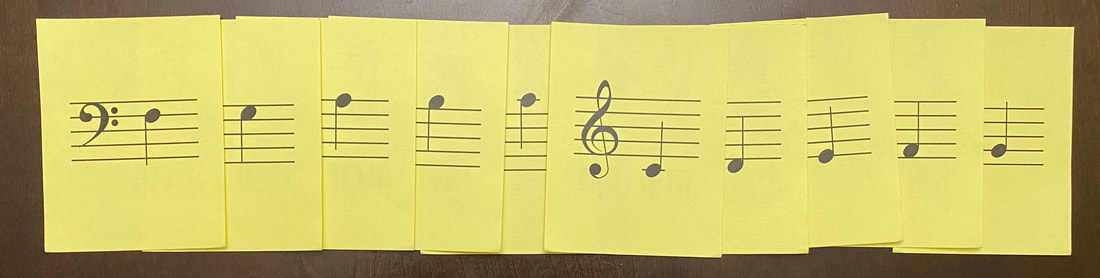

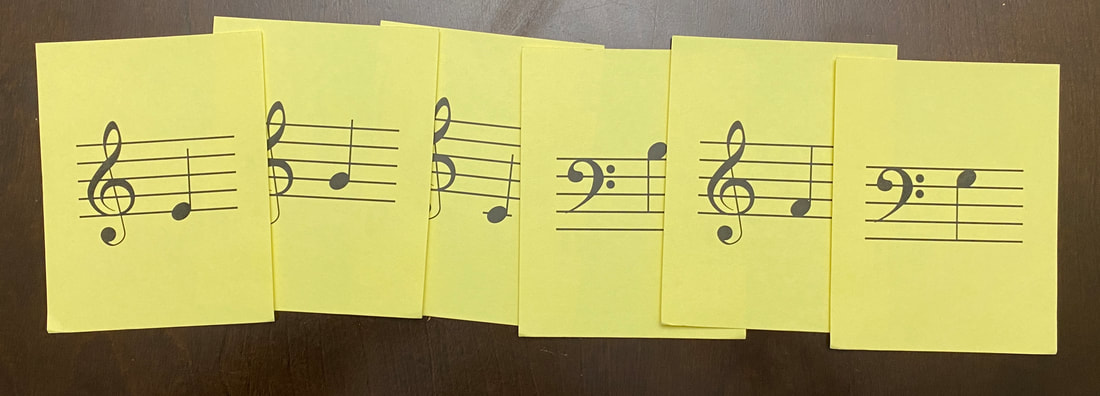

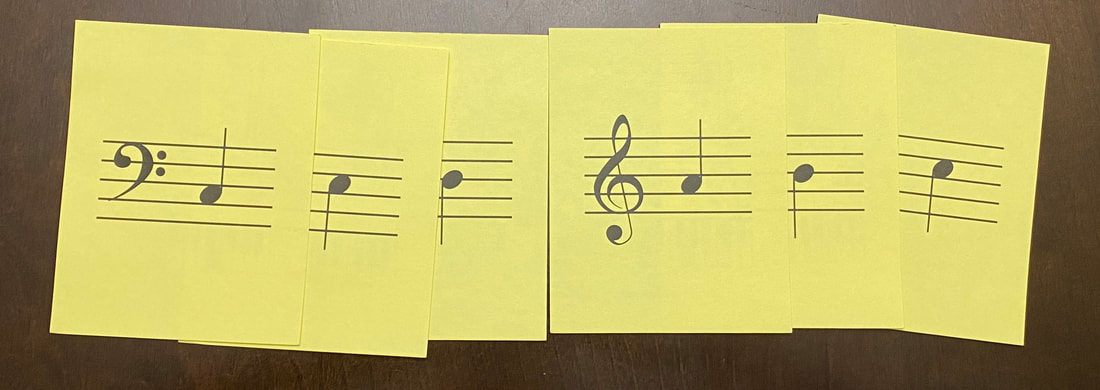

First, filter through your flashcards and select the ones that form the middle c position:

Here's the keyboard guide for comparison.

Two reasons why we use this position:

We're going to keep the cards in this sequence and have each answer side showing.

Side note: play all treble clef notes with your right hand. Bass clef notes with your left hand. Remember this rule when you start to play beginning level sheet music.

Challenge comes later, for now we want some quick wins - my philosophy for first-timers is to encode success. Just get familiar using the cards to play each note in the easiest way possible.

But if you find this too wimpy, feel free to skip ahead to any part of this section (you wild thing you).

From here, we're just going to add a layer of difficulty, step by step. Once you're able to easily identify (and play) every note, shuffle the cards so the patterns are random:

This is more realistic since, in real music, you usually won't see notes in any detectable.

When this gets easier, practice with the no answer side showing.

A word of caution: ALWAYS doublecheck your answers. I'm assuming you're doing this on your own, so if you don't confirm your results you'll assume you're getting everything correct - only to realize MONTHS later that you've been doing it wrong.

Seriously. Check your answers every single time. The last step is to repeat this entire process - answer side up, easy patterns, etc. - without the keyboard guide. Once you go through this sequence without the guide, just go back to square one - put the guide back on and repeat all the steps in order, but with a larger range of flashcards.

Repeat this process until you're able to read every flashcard.

Houston, We Have Ignition

I mentioned earlier that you might be one of those unfortunate souls who memorized the dreaded mnemonic.

Fear not, for I have your cure. The good news is that it's really easy to implement. The bad news is that it takes a lot of self-discipline to do by yourself: doing this alone is a really unnatural process, it's going to feel like you're "force-feeding" yourself. Anyways, this fix has to do with the last ten seconds of every year - the (New Year's) countdown. Now, I initiate countdowns - usually 3 seconds - when I notice a student is taking too long to identify the notes. When this happens, there are two things going on:

Counting down eliminates both of these problems. The reason has to do with perceptual processing: your brain will autocorrect your initial mistakes over time - as long as you're double-checking your notes. And this happens at a subconscious level: the short countdown eliminates conscious thinking. If you're a bit of a perfectionist, this is going be uncomfortable for you because you are going to make a LOT of errors - it's helpful to just think of every attempt as a random guess. The first time I have a student go though this process, they normally miss 90% of their notes. But we stick with it week after week and they eventually reach 100% accuracy. They get so good we can whittle the countdown to a single second! And keep in mind we do this just once every week (each lesson). So if you find yourself in the same situation as my students - analysis paralysis or referring to a "base" note - then try this out at any stage of your note reading. Take a leap of faith and mnemonics will become a distant memory - since you won't even have time to think about it. But like I was saying, this is hard to pull off on your own. You have to have the discipline to play a key, any key, once you reach zero - I suggest having someone help you out initially. By the way, if you think perceptual processing is interesting then there are 4 other amazing practice concepts that will blow your mind. Read more here. Conclusion

So there you have it, the method I've been using to get students fluent in note reading for over a decade.