|

This article contains affiliate links... If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

​

When I first became a piano major in college, I worked like I had a fire lit under my bum.

I can't recall another time I extended so much effort in my life, I was practicing 6-8 hours every day - including many weekends - for years. But it makes sense: as a first-generation Korean-American, I come from a working class family - physical exertion was the only way. My professor lauded my work ethic, my colleagues - supposedly - admired my discipline and I progressed immensely through brute force alone. But anyone in their right mind would've hated my approach. They wouldn't just balk at the crazy amount of hours I put in, but dismiss my practice philosophy (if I even had one) as tedious and boring. To which I completely concur. Looking back at those days, I can objectively say I wasted more than half of those hours I spent practicing. If I had a time machine, you bet I would go back and do things completely differently. Fact is, the conventional, traditional approach - repetition after repetition a.k.a. no-painno-gain - is still the dominant one today. To succeed, you need bust your butt day after day ... month after month ... year after bloody year. If you put in the time, everything will work out. So suck it up buttercup, put your hours in and deal with it - that's just the way it is. Only it isn't. The truth is that it's not going to magically work out for you if you just put in the hours alone. The good news is that there's a better way, one that's less painful and way more fun. The key to practice that sticks is not endless hours of mental and physical exertion. It's using time-proven, science-tested strategies based on variety, maximum concentration and enjoyment. So in today's article, I'm going to share the concepts that have radically changed the way I teach and practice piano. If you apply these concepts, I'll bet you my left eyeball that you'll get incredible results - results you wouldn't have dreamed were even possible. Here's the gameplan: in each section, we'll go into depth on a single concept. I'll not only provide explanations and benefits, but examples of how I've applied each concept in my personal and professional life. I hope you'll be able to take what you learn here to craft your own personal, strategic, and fun sessions for piano success - whatever that means to you. Ready to have your mind blown?  How to Break Down Piano Practice

Question: How do you eat a pizza?

Answer: One slice at a time. You could be a smart aleck and say one bite at a time, but the point is you don't just inhale the whole thing - unless you're a competitive eater. Yet this is how most people approach work, and what's the result? Procrastination becomes our best friend and worst enemy. This is because our minds aren't built to deal with huge, massive projects in one go - we have a difficult time processing a ton of information at once. For instance, pay attention to how you feel when I mention:

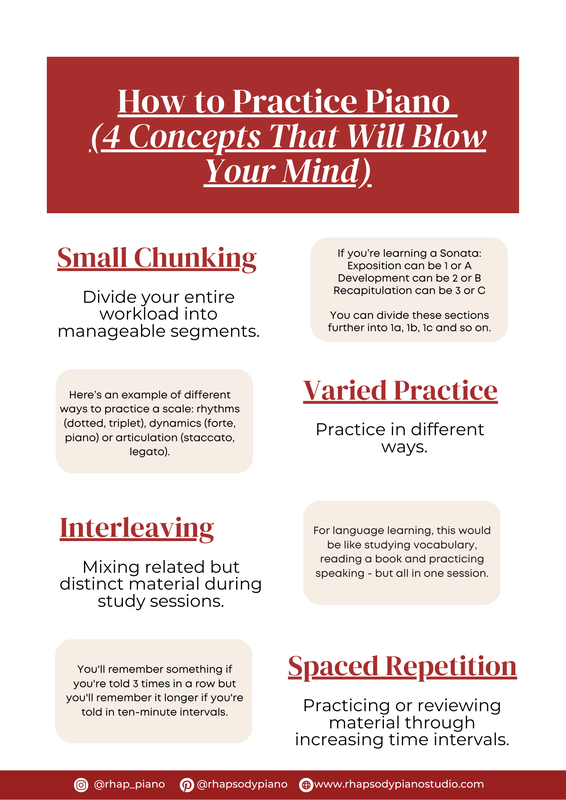

The reason your eyes are glazing over is because it puts your mind in a sink-or-swim mentality. The solution is to small-chunk: divide your entire workload into manageable segments. This comes naturally for us anyway. For example:

Stories have a beginning, middle and end. Songs have hooks, verses and choruses. Each house is built brick by brick. Small-chunking not only creates a structure that your mind can make sense of, but a process that is more efficient than the normal guns-ablazing, damn-the-torpedoes approach. I've used this idea to build many long-lasting habits over time. For instance, at one point in my life I was meditating up to 30 minutes a day. But I started with 5. My current stretching routine is a little over a half hour. Yet it began as 10 seconds (per stretch). Stephen King suggest the same for writing, which is to do so one word at a time. Pretend you're working on a sonata. Most students default to practicing the whole piece from beginning to end. Now, if that sonata was a table then this would be like putting all your attention on the surface: you can enforce the top as much as you want, but if even one of those legs are flimsy then the entire edifice will collapse. Practicing in small chunks strengthens each column and ensures your construct will stand on solid ground. Think of each leg as a portion of your sonata: the technical name of each part is exposition, development and recapitulation. But you don't even need these terms - you can simply use numbers or letters. For example:

Here's where it gets interesting. Now that you have your major (macro) sections, you can divide them even further (micro). If you're using numbers, then your exposition becomes 1a, 1b, 1c and so on. If using letters, it becomes A1, A2, A3, etc. Besides making sure your sonata is sturdy, here are some other benefits you'll reap by small-chunking:

Making these divisions are especially valuable when working from memory: when you memorize each chunk separately they become "signposts" to guide you during performance. It's kind of like including enough pit-stops on a road trip - even more paramount if you have a weak bladder. Now, a word of warning: don't mistake difficulty for attention-span. This is another reason why it's a bad idea to practice your entire piece from beginning to end - this results in a strong intro, mediocre middle, and weak ending. Once you've subtracted enough - created enough signposts and distilled a unit to a manageable nugget - then you add. Notes become measures, measures become phrases, phrases become a micro-section (A1, 1a), micro turns into macro (A, B, C, 1, 2, 3) and eventually you have the whole thing. Let's use technique as an another example. If you're learning a traditional 4-octave scale, start from the smallest unit. When I teach this to a student, this is the progression:

What about rhythm? No problem. We can even use this approach for one of the most difficult patterns - polyrhythms (2 different rhythms occurring at the same time). Just start with a single beat - play a triplet in one hand against 2 notes in the other. After this gets easier, add another beat. Rinse and repeat until you're able to do pull off an entire string. If you start small enough, anything is possible. Onto our next concept.  The Spice of LifeBruce Lee once said, "I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times." This is something everyone can understand: single-minded, undistracted effort. Due to my culture and heritage, I was basically indoctrinated into this work-till-you-drop mentality. Not that I'm ashamed of it in any way - I'm proud of the discipline I inherited working alongside my family in our businesses. So when I got serious about piano, I was like a hammer that saw everything as a nail - and my practice was just as straightforward: if 5 reps weren't enough I'd try 20, 50, 100 ... to infinity and beyond! But like I said in the beginning of this article, all that hard work led to ... bare results. It makes you wonder, why be so industrious if the returns don't justify the means? So what's the alternative to this nose-to-the-grindstone work style? The secret is to tweak Bruce Lee's original saying:

Allow me to introduce our next concept: varied practice. I came across varied practice in the book How We Learn, by Benedict Carey. It's a book you can't miss - the next 2 concepts I'll discuss are also from this book. Here's one of the studies: Researchers at the University of Ottawa observed 36 eight-year olds who were enrolled in a 12-week Saturday morning PE course at the local gym. They split the group into two. The exercise of choice was beanbag tossing. The first group was allotted 6 practice sessions. For each session, they were allowed 24 shots at a distance of 3 feet. But the second group varied their practice. They had 2 targets to practice on, one target from 2 feet and another from 4 feet away - this was the only difference. At the end of 12 weeks, the researchers had both groups perform a final test. The caveat was that it was from the distance of 3 feet, to which the first group was already accustomed. Before you object to the fairness of the test, check this out: despite the disadvantage, the second group still outperformed the first (3-feet only) group. As a Lakers fan, this makes me wonder how many more championships would have been won if Shaq varied his free throws. Anyways. This isn't limited to physical activities, you can also vary environments. A college student can use this on a smaller scale. Let's say they're struggling with a paper or project - in this scenario you can deploy the Grand Gesture. This idea comes from Cal Newport, author of Deep Work and other noteworthy books. In Deep Work, he shares how J.K. Rowling finished the last part of The Deathly Hallows by checking into the five-star Balmoral Hotel located in downtown Edinburgh. The hotel was not only her inspiration for Hogwarts, but provided a nice change of pace from house chores and loud kids. She ended up staying ... until she finished the book ... at a cost of more than $1,000 per night. Now, if your dinner is usually top ramen then you barely have the funds for a Motel 6. But on a smaller, more affordable level, you can retreat to the corner of a library or local cafe. You can also mix things up by changing the way you work. I once read that Ernest Hemingway wrote standing up. So what did I do? I purchased a standing desk and the change of pace has been super. It's nice to get off my butt as much as possible, considering how much time I stay seated teaching private lessons and practicing piano. And the change in physical posture has a clear, positive effect on my productivity. So we've covered beanbag tossing, changing locales and writing - now let's talk piano. Furthermore, I'll demonstrate the utility of varied practice with one simple pattern. Here are all the different ways you could practice a single scale:

Like small-chunking and the other concepts you'll learn today, varied practice is only limited by your imagination.  Productive Multi-TaskingWhen TiVo came out, commercials were instantly made irrelevant. All of a sudden, you didn't need to sit through endless advertisements. And smartphones have taken things to a whole new level. These devices have made things a thousand times more convenient, but that convenience comes at a price - the scattering of our attention. I mean, people can't even wait in line for one minute before zombifying themselves on their screens - swiping from app to app, switching from video to video. However, it might surprise you when I say this is the general idea behind our next concept: Interleaving. Out of all the concepts you'll learn today, this is one's my absolute favorite and I'm convinced you'll love after you give it a try. Interleaving is mixing related but distinct material during study sessions. If you were learning to cook, this would be like chopping vegetables, listening to a cooking podcast, reading a recipe book, and watching video demonstrations ... in one session. It's similar to varied practice. But whereas varied practice is more vertical - sticking with a single problem - interleaving is lateral, moving across different problems with the same goal. Instead of climbing up a ladder, you jump to a different one. Here's a second study from How We Learn. Researchers tested 2 different groups on a painting project/assignment:

Just like the last study, the second group (mixed-study) outperformed the first group (blocked-study) - 65% to 50%. The researchers ran this trial on a separate group of undergraduates with the exact same results. If we applied interleaving to exercise, it would look something like cross-fit or what's called a "bro set." Instead of repeating an exercise with rest periods, you immediately switch to a different one. For example, doing squats after a set of pushups, or jumping jacks after crunches. When I first discovered a love for books, I intuitively used this strategy to read for hours at a time. When I got bored with a book, or my concentration waned, I'd immediately switch to another one. Which is why I always had a minimum of 5 books on me at all times. Here's how I apply it to my language studies. I schedule my sessions using the pomodoro technique. Each block of time is spent on one of the following categories:

Ideally, I'd be able to do this all in one session but I usually sprinkle these activities throughout the day. You can take it a step further by interleaving un-related activities. In one session you could:

And there's no specific order to do these in - many times I'll just show up to my desk and do what I feel like in the moment. But perhaps the most important benefit is that it transfers to the real world better. It's like that saying about school, what you learn in the classroom stays in the classroom - the content you learn from a textbook doesn't automatically transfer to your real life. Canine enthusiasts know what I'm talking about. When you're training a dog, you need to put them in a variety of situations. Your pup might be an angel at home, but in a new place with all kinds of stimuli all that coaching will go out the window. This is also why so many of my students will say the same thing week after week, "but I played so much better at home." It's easy to rattle off successful performance after performance at home, but at a public venue it's a different story. So instead of controlling every scenario, interleaving introduces randomness, which is more like the real world. This grates against our nature because we're pattern-recognition machines we need an explanation for everything (even if there isn't one). But like Neo says in The Matrix, "there is no spoon." So here's how I use interleaving to practice. My regimen consists of:

For musicianship I could try transposing a Bach minuet into a few different keys, playing through chord progressions and working out some jazz harmonies. Technique consists of playing scales, etudes, and arpeggios but in a random order - or even jumping back and forth from scale to etude to arpeggio. Repertoire can comprise multiple genres as well as different levels of difficulty. But as much fun as I have in my own daily practice sessions, I believe my students get much more enjoyment out of interleaving. Here's what a typical lesson looks like:

Most times I'll follow a certain sequence, other days there's no preset order. The unpredictability keeps them on their toes and the momentum generated helps us fly through our lesson time - all while keeping their concentration at a maximum level.

The combinations that interleaving allows you, unlike my credit cards, are limitless.

Space, The Final Repetition

We're all familiar with the phrase, "don't just stand there, do something!"

But this final concept advocates the opposite, "don't just do something, stand there!" This is the spacing effect or spaced repetition. This is why:

Now, this time a story from How We Learn. In 1982, 19-year-old Polish college student Piotr Wozniak built a database of about 3,000 words and 1,400 scientific facts in English (he really wanted to learn the language). He experimented by structuring and scheduling the material in different ways. Soon, he noticed a pattern: after a single session, Wozniak could recall a new word for a couple days. But if he restudied it the very next day, that retention lasted for a week. And after a third review session (2 weeks after the first) he could remember it for almost a month. In other words, you'll remember something if you're told 3 times in a row - but you'll remember it longer if you're told in ten-minute intervals. Around my home, this is a natural phenomenon: my wife will hum the melody of a song she just taught a student earlier that day ... ten minutes later I'm humming the same (damn) tune subconsciously. Spaced repetition is by far today's most time-efficient learning strategy: you're able to learn and memorize better - and more easily - by spreading review sessions over increasingly longer periods of time. It's like an investment compounding, only it's your brain. Fluent Forever is an app that uses this to great effect. I practice with it daily and it's how I've been able to keep thousands of words memorized in a few different languages. This is something I naturally do with (good) books. If it's worth my time, I'll re-read a book after a spell. And almost every time I come away from that second reading knowing more. As a side note, there's an adage that many serious bookworms know about: you get more out of great literature the more times you re-read them. It's also how to not kill yourself as a writer: the most useful piece of advice I ever read was to just stop entirely when you get stuck and come back the next day. Yes people, giving up is an effective technique. Here's how I apply spaced repetition to piano lessons. First, I look at it from a micro level. If a student is having a hard time with a difficult passage, I'll have them practice juuust until they're near their "breaking" point. Right before they reach that moment, we'll work on something completely different. After about 5 minutes or so we come back to the very same passage and nearly every time you'll hear them say, "hey, it's easier for some reason." At which point you silently mouth, "spaced repetition." Second, the macro level. This is my go-to concept when preparing a student for a recital, especially if it's their first performance. For first-time recitalists, it's beneficial to schedule their mock performances as far ahead as possible since the wait periods in between practice rehearsals will be getting longer and longer (to utilize the spacing effect properly).

This lets us take full advantage of spaced repetition - the more cycles a student goes through, the better the result will be when they step on stage for the very first time.

This also works equally well, if not better, for memorization. Ever since I became a devoted spaced repeater (tempted to say space cowboy), I've been able to keep repertoire memorized with just a few review sessions per year! To see examples of how I do this, grab a copy of The Rhapsody Practice Guide - which is included in the Rhapsody Starter Pack (sign up for the newsletter and you'll be taken to a page where you'll receive it at a discount). However, this concept really shines when introducing brand new material to the student. As a teacher, if you internalize this concept and are able to teach it well, you can use this for everything:

And what's even more ridiculous ... they don't even have to practice at home. I once had a student who was really bad at note-reading (almost as bad as my sightreading). For the life of me he would never practice flashcards at home no matter how many times I begged him to. So we only did them at the lesson - it took him 6 months to read basic notes. For 6 whole months, we did flashcards once a week. It frustrated me to no end, but the point is we eventually got there. Moving on. Here's a sample plan involving scales - but remember you can extrapolate this to just about anything. Keep in mind this is a situation where the student has never played a scale before. I'll have them play a one-octave scale once at the lesson (with one hand). Then they'll play it again ... a week later. If all goes well, we'll do more spaced repetition within the lesson. If we're not at this point, we just wait another week to try again. Once they're past this stage, I can then assign the student that scale to practice for the entire week. But I only do this if I'm positive they can play correctly. This is has to do with encoding success practicing correctly from the start. It's also because I give them no instructions whatsoever. Seriously. If you opened up their instruction book, all it would say is, "technique: one scale, one octave, hands separate." Then we baby-step this process until they're able to practice both hands to at least two octaves. Sometimes the lazy approach pays off.  Less Is More

The mainstream advice for success is to add, add, add. But doing this turns you into the "busy" person at the office - having a million things on your plate while contributing little value.

But it's really about elimination - what not to do. As someone who spent their entire childhood in the family business, this was a hard pill for me to swallow. I always believed that you could achieve anything as long as you worked hard for it. But I took a look in the mirror one day and realized the results didn't justify the time I (wasted) spent.

Most people will take what they read today and promptly forget it. They just don't want to believe you can get more done with less effort.

I hope you're not one of them. Toiling by the sweat of one's brow says one thing, it's my way or the highway. But what's the point if that highway leads you off a steep cliff? Isaac Newton once said he succeeded because he stood on the shoulders of giants. The smartest way to achieve success in this world is to take the lessons that great people before you have learned. In fact, to go through the same difficulties even though it's avoidable is stupid. If you got something out of today's article - heck if you even read this whole monster of a post - it means you value your time. Look, I love hard work as much as anyone else. It feels great to be productive, to be exhausted at the end of the day knowing you left nothing on the table. But between practicing hard and practicing smart, I'll choose the latter every single time. Process over results. Yes. But that process is useless if you're not getting outsized returns. So here's a toast, cheers to the preposterous results you'll get if you use what you've learned today. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

0 Comments

This article contains affiliate links... If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

Best Way to Learn Piano

After a student piano recital, one of my wife's clients made a remark about how "professional" my students' hands looked on stage.

That client was talking about hand posture. My technical explanation: to deploy the hands and fingers in an optimal way to play with proper, relaxed technique. Funny thing is ... I've never taught hand posture. Sure, I make corrections here and there during lessons but it's hardly a main focus. So how is it that most, if not all, of my students develop great hand posture? Drum roll please ... because they watch my YouTube videos. When I first started teaching privately, I was eager to find any tool to help my students succeed. So I experimented with recording videos and uploading them to YouTube. Fast forward to today, this was one of the best decisions I've ever made. Whether you're a beginner, intermediate or advanced pianist, I'm convinced that online videos are the greatest resource available to you today. So in the rest of this article, I'm going to share the top 3 reasons why online (YouTube) videos are the best investment of your time when learning piano. At the end of this post I'll also include a free link to my Faber Collection Guide, a curated list of the most popular sheet music series I've ever taught.  Vision Is KingDr. John Medina - author of Brain Rules says that "vision is king." This is true not only for adults, but even for children at the youngest age - babies immediately begin using visual cues to learn without being taught a single thing. And according to further research cited in the book, visual processing takes up about half(!) of your brain's resources. It also doesn't matter how well-honed your other senses are:

Additionally, another test showed that people could remember up to 2,500 pictures with 90% accuracy when shown the same images several days later - more unbelievable is that they saw each picture for only 10 seconds. Further research from the book indicated that presentations given without pictures - purely text or oral - were far less efficient than presentations given with them. For oral presentations, people remembered 10% of what they heard after a couple hours. When pictures were added, their memory jumped to 65%! This is also a prime strategy when learning languages. A valuable book on language acquisition, Fluent Forever, advises aspiring polyglots to pair words with pure images instead of direct translations. Imagine you saw the word caballo (Spanish for horse) on a flashcard. When you flip that card over, you should see a photo of a horse and not the definition in English. You remember more easily by not relying on a word-for-word translation. But there's more to this story. We have these things called mirror neurons: specific neurons that get fired in our brain whenever we simply observe an action. This means by merely watching someone do something, we almost feel the same sensation of having done it - monkey see, monkey do. This article from themusiciansbrain.com discusses this in more detail and I highly suggest you check it out after you finish up here. But here's the highlight I remember the most: these so-called imitation neurons are activated in a musician's brain ... even without sound. WITHOUT SOUND!!! This partly explains the phenomenon behind mental practice. For example, if you saw me out-and-about you would notice I tap my fingers a lot. But what you think is an annoying habit is actually me playing a Beethoven sonata. By the way, this is a frequent go-to technique for professional musicians when they don't have an instrument to practice on. Let's take this idea even deeper. Here's a story from the book, The Talent Code. The author, Daniel Coyle, met Carolyn Xie, who was a top-ranked Chinese-American 8 year-old tennis player in the entire country (at the time). He noticed she had the typical tennis prodigy's game, except for one thing ... her backhand. Instead of hitting tennis balls with the usual two-handed grip, she hit them one-handed ... Ã la Roger Federer (one of the greatest tennis players ever). In fact, she did it exactly like Roger Federer. When Coyle pressed her on this, she had no idea what he was talking about. He was taken aback by this curious statement, but later discovered that Xie and her entire family were rabid Federer fans. In her short life, she had watched nearly every single match Roger Federer ever played - and simply absorbed his backhand without realizing it. So in theory, this is why my students develop impressive hand posture - by absorbing mine through videos. A picture most definitely is worth a thousand words. But we not only mimic everything we see, we also emulate what we hear. To illustrate, a short vignette from my personal life: I once visited a colleague in Chicago, who had recently befriended two amiable Irish lads. And wouldn't you know? Just after a day I not only picked up their slang, but their accent - along with a healthy appreciation for Guinness. This is why videos are such a powerful resource: they tap into your vision as well as your hearing. And remember, because of mirror neurons they also tap into your tactile (touch) senses as well. A formidable triple-threat combination. Strike a Pose

Now when it comes to learning piano, or anything else for that matter, I submit to you what I believe to be the most important question ever:

If you're attempting to learn on your own, this question gets magnified tenfold. This wasn't much of an issue during the classical era. During those times, piano students reportedly had lessons every day (they also never had smartphones, but that's a topic for another time). Contrast that to today: most students only have a half hour lesson once a week - which means they have 6 days to get things wrong. In a perfect world, daily lessons are the way to go. But who can afford that? This is the main reason I started recording videos and posting them on YouTube. I was not only frustrated with students doing the complete opposite of what was instructed, but realized they needed a model for reference. In laymen's terms, they needed an example to imitate (there's that word again). This makes videos the perfect example - they're virtual demonstrations students can access at any time, any place. I also don't say a thing in these recordings - the majority of my videos are just me playing the entire song or piece from start to end. Explanation is unnecessary! Let's read on to see why this is the case. In the book The Inner Game of Tennis, Timothy Gallwey, author, shares how he taught fifty-year-old beginners of tennis to play decent games ... ... within 20 minutes ... ... without a single word of instruction! He taught with his mouth shut - something a lot of educators should do more of. Side note: Gallwey also co-wrote The Inner Game of Music, a highly suggested read on the psychology of performance. What better way to learn, especially something like piano, than being shown exactly the way it's done? As an aside, I find it sadly hilarious when I get YouTube comments on a certain video complaining about the accuracy of my playing - while my students use the exact same video for great results. Some people will lie to themselves no matter how much concrete evidence is staring them in the face. But remember ... the tape doesn't lie. Videos are not only a safeguard (hopefully) against human bias, but also remove much of the complexity in piano playing. This is particularly important for a beginning student: the less they have to think, the more mental resources they have at their beck-and-call (which hopefully translates into high-quality practice). It's just like productivity - the less (trivial) decisions you need to make, the more concentration you have in reserve. For you more experienced players out there, videos can represent benchmarks rather than models. But even if you're at the intermediate level or beyond, there are always going to be more challenging pieces for you to learn - so you'll still need tools like videos (or audio recordings) at your disposal. Lastly, videos are the most accurate model for learning piano because they satisfy all the requirements for corrective feedback, which - according to Scott Young - is the best form of feedback. Here's the definition from his book, Ultralearning: corrective feedback tells you what you're doing wrong and how to fix it. Now, I'm not saying you'll be able to do this right off the bat. When I teach a complete beginner it can take anywhere from a week to a month for them to get the hang of videos for self-study. But no matter how long it takes, they always get there. One last word of advice: if you're learning without the aid of an expert, you're going to need a BOATLOAD of patience - and objectivity.  Instant EducationJ.S. Bach once walked 250 miles to hear the music of master organist Dietrich Buxtehude. Compare that to today - some people won't even drive 5 miles on the weekend to get food (totally not talking about myself here). We'll naturally (lazily) seek the most convenient option available - unless your last name's Bach. For example, see:

Services you can access in seconds, apps available in the palm of your hands, products brought to your door with a tap of your finger. Even when you're out-and-about, and not burying your face in your phone, what food options do you notice? A fast-food joint lollapalooza. Admittedly, healthy choices are becoming more abundant but junk food is still the winner by a land slide - because it's cheap and quick (convenient). And it's the same with my piano studio. The egoist in me would like to boast that people come to me for quality, professional teaching. But 99% of the time it's because ... I'm down the street. So here's the most important reason why online videos are an unrivaled resource: they're easily accessible. What else is more straightforward than opening your YouTube app? With a little practice, the whole process could probably take less than a second (not that you should try). And what an amazing place to learn it is! You can find topics on everything. For me, YouTube has been the single wellspring of information I've both spend the most time on and learned the most from (besides books). It's amazing that I can search up a video on an established author or noteworthy thinker, instead of walking 250 miles. And even better is when a YouTuber actually documents their whole journey - so you know their results have been field-tested. This is super useful for when you need to fix something around the house (saving hundreds of dollars) or tear apart a dungeness crab (tasty) for the very first time. Not to mention that it's all FREE, so don't you dare complain about ads. Now, this doesn't mean you shouldn't ever shell out cash. Once you vet the source, something like an online course can be a shortcut in terms of the learning process. Still, I love the fact that there's no price tag on what we can learn these days. The easier a tool is to access, the more you'll use it. So unless something better than YouTube comes along, that's what you'll be using for the immediate future. Best PracticesNow onto some practical suggestions, as in how to best utilize online/YouTube videos. There are four ways to learn with videos:

If you're a beginner, you most definitely want to watch before you play. It's because:

I can't say this enough: make sure you develop proper practice habits from the start. In my experience, it has always been easier to teach a student from scratch. hen I get a transfer student for the first time, we usually spend the majority of piano lessons fixing bad habits they've developed. For example, I have an amazing student who just started with me 2 months ago. But during the waiting period (a year or so) before our first lesson, he self-taught himself with YouTube videos. Though my jaw dropped when I initially saw what he could do, our lessons have been geared towards correcting faulty technique. Now, if you're at the intermediate level then you can watch videos after (or while) you try a new piece out - since your skills are more established. You can also use videos to practice more challenging music, repertoire that's beyond your current level. It's a superb way to amplify your progress. Next, you can view videos away from the piano - when you're not physically practicing. This is very handy because you can tap into spaced repetition. You do this by watching throughout the day at different times. So instead of looking at a video 5 times in a row, you'll understand a LOT more by spreading those repetitions out. This method was scientifically researched. In How We Learn, studies showed that traditional repetition actually made you worse. By the way, you can also apply spaced repetition to physical practice. Lastly, you can play along with the videos (simultaneously). For obvious reasons, this is the most precise way to practice: you hear all the correct notes and proper rhythm in real time. A word of warning though: you can make a massive amount of progress with this approach, but be careful not to use it as a crutch. Mistake-free, accelerated learning is exhilarating! You want to avoid a situation where you constantly have the answer handed to you. Without challenge, it's not real learning. So I suggest using a combination of all four methods described. Variety of practice is what will lead you to tremendous improvement. Fin

As promised, click this link for recommended sheet music. Videos have made a stupendous difference for my students, so I'm excited to see what you'll achieve with them!

I can't help but feel a bit jealous, if I had YouTube growing up I'm convinced I'd be a radically different pianist today. Ah well ... it's the journey that counts. So I rest my case. I hope I've convinced you that online videos as the best modern resource we have to learn piano - they've definitely become a permanent staple of my teaching process. When I first recorded a simple YouTube video for a single student, I never thought I'd end up recording a complete curriculum for my entire studio - or even start my own YouTube channel. But ... you can bet I'm always on the lookout to see what amazing new learning tool is on the horizon. Even as an old dog, you can always learn new tricks. Happy Practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

Help support the blog so you can continue receiving content and free guides.

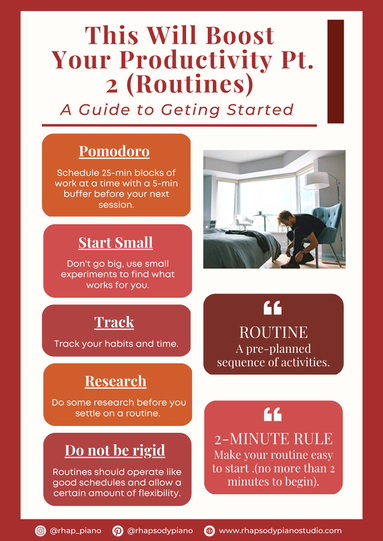

This article contains affiliate links … If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you! In last week's article, I discussed the importance of having aritual for productivity. Rituals are the spark, while routines are the logs that keep things burnin'. One of my idols, Alex Hormozi, actually argues that rituals and routines are a total waste of time. But I don't believe that's true. In fact, I think that type of thinking is dangerous. It's because rituals are like superstitions. It's not really why you believe in them or not, it's the function they serve. For example, walking under a ladder is a traditional form of "bad luck." When people ridicule this, they're missing the point. It's not really about bad luck - it keeps you from getting hurt. Here's another one: an apple a day keeps the doctor away. No, the apple isn't the cure all to all your health conditions. The point of this saying is to get more healthy food into your diet. Rituals are just as necessary as superstitions and routines are just as necessary as rituals. For instance, what do you do at the beginning of exercise? You warm up your body so you won't get hurt. You also warm up for your piano sessions to get good results from what you practice. Useless? I think not. The Point of a Daily RoutineNow before we get into the benefits of a routine, how should we define it? For me, simple is best: a pre-planned sequence of activities. By defining it this way, even your entire work day can be a routine. Just as I mentioned in last week's blog post, keeping our definition broad creates more versatility. This means routines are adaptable - you can create them for anything. These activities can range from work-related tasks, personal projects, or even getting to bed on time. FYI, the bulk of my own activities are learning projects and habits. Even better, you can think of learning as an actual habit. Doing this allows you to take principles and concepts from books like Deep Work and Ultralearning (more on this later). Daily Routine: Deep DiveLet's go deeper on why we need routines. In a sense, routines are like schedules. Schedules help us maintain a sense of order - imagine going to work without knowing how many hours you'd be staying. And we gravitate to things like this because we're pattern-recognition machines. We have a difficult time dealing with randomness. For instance, my dad often spoke to me about how good his friend's daughter was ... at slot machines. That's like saying you're a really good coin-flipper. We have an incessant need to have an explanation for everything and anything out of place has to be put in some type of order. But routines aren't so much about making every single day as perfect as as possible as they are a way to bring structure to our lives when things get chaotic. And they also help you think in small chunks. Huge, massive projects feel overwhelming, mostly because we envision the entire thing from start to completion. If I had to write this article from start to finish, my thoughts would soon become suicidal. The optimal approach is to break it down into manageable segments. And once you know what these segments are, then you can lock them into a chain of sequences (routines). Next, some benefits. The ProsBy having everything planned ahead of time, you get rid of decision fatigue. I believe the bulk of people's time is wasted on making decisions. One form of decision hell is something we all know too well. For example, my wife and I go through the same song and dance every weekend - what do you feel like eating hon? Sometimes having too many choices (see: Yelp) is worse than not having enough! But I digress. It's much better to accelerate decision-making or abolish it altogether, so you can conserve all that mental energy for the important work that matters. As I've said before, expectancy creates productivity. When you know what to expect, it's easier for your mind to lock in with the right type of focus. It creates a "mind like water" as David Allen says. Another thing I'll never get sick of repeating is that productivity - like creativity - is a process of elimination. Many times people are looking for things to add: this app, that tool, etc. But too many choices causes confusion (see: Yelp). Instead, think about what you need to remove. This is why your work environment matters so much. The less clutter you have (both physical and digital) at your desk, the simpler it is to get started. It's easy to work when there are no distractions. So if your work environment is about eliminating visual distractions, routines serve to eradicate mental ones. It's like programming your brain: you just need to execute one command after the other. CautionIf you have no idea where to start, and need a template to follow, I'll share mine in a minute. But before that, a few general guidelines. Don't be rigid, unless you want a nervous breakdown. Routines should operate like good schedules and allow a certain amount of flexibility. Just think of yours as a compass to point you in the right direction. There will be moments where you lose track of time or get behind on your workload. When that happens, just revise, reprioritize and get back on track. If you're able to accomplish 70-80% of what you set out to do, I'd say that's a great day. One last word of advice: spend time on preparation before you settle on a routine. This could mean gathering all the right tools (see next section) or envisioning your day unfolding realistically. A good suggestion is from Scott Young's Ultralearning. He recommends you spend at least 10% of your total projected time on research. For example, if I'm going to spend 40 hours learning a new language then at least 4 hours of that will be spent on groundwork. Even if you aren't planning a massive undertaking like becoming fluent in Spanish, as little as 10 minutes of upfront exploration can you save hours of wasted time. BlueprintHere's how I go about my routine. I schedule everything in 25-minute blocks. This is what's known as the pomodoro (Italian for tomato) technique, so-called because the inventor, Francesco Cirillo (also Italian) used a tomato-shaped timer for work. Why 25 minutes instead of 30? This is to include a 5-minute "buffer" which acts as a safety-net. There will be days where you execute everything perfectly, but most of the time things will be dropped on your plate at a moment's notice. For example, you might suddenly need to call someone back, shoot off an email or, file this under TMI, battle the toilet because of those nachos you ate last night - bad decision (but somehow still worth it). If you don't have these buffers in place, any small disruption can unnerve you and throw off the entire day. That's also why it's a good idea to start small. Be ambitious, but temper that with reality. Use small experiments to find out what works, lest a disaster implodes in your face. The other reason, at least at the start, is that you want to accomplish everything you set out to do. This is why checklists are so satisfying - when you finish every last bite on your plate, you can't wait until your next meal. To accomplish this, focus only on one thing at a time. For example:

And so on. For piano sessions, this could be:

You might devote the first 30 minute session to technical practice (scales, arpeggios), another for musicianship (ear training, harmony, solfege) and finish up with repertoire (songs or pieces). Or you could schedule 1 or more hours on one area. For example, musicianship could be divided into 3 blocks of ear training, harmony and solfege. For repertoire, you could work on a Beethoven, Chopin and Debussy piece. Technique could be split into arpeggios, scales and etudes. You get the picture. However, I don't recommend this last option until you've developed enough concentration to handle the workload - it takes a lot of focus to pull off these longer sessions. ToolsNow, I happen to have a ton of digital tools at my disposal. However, I love using a physical habit tracker for the following reasons:

And when you see those x's tic-tac-toeing across page after page, it's easy to stay motivated and disciplined enough to keep the chain going. But you don't have to limit this to habits or things you're learning. You could just as easily include responding to emails and more technical tasks - or even remembering to take your supplements every morning. In addition to a habit tracker, you might want to track your time - the app I use is Atracker. I've previously covered why it's useful to measure what matters as this helps you keep records of what you spent time on. For example, I have data on every minute I spend on work and learning. Once you have a record of your time, you can see if you've been using it well (your target areas) or if you're falling behind. You either keep doing what you're doing or allocate your minutes to the things that matter. Tick, Tock

Lastly, it can be useful to have several routines scheduled throughout the day. For example, my work routine might be different than the work I do in the evening. Or it can be a continuation of the same routine - to squeeze in more valuable hours before bedtime. A third option is to use a routine to recharge. This is the purpose of my stretching and meditation session before teaching. I'm usually exhausted after my morning-afternoon pomodoros, so doing this gives me a second wind. If you're interested in more, see my blog post where I utilize this concept with ideas from Deep Work. With this plan and these tools, you have a powerful formula for productivity and discipline. ConceptsNow, I'm going to share a few concepts and strategies that will not only boost the quality of your work sessions, but act as safeguards. The 2-minute rule from Atomic Habits will help you maintain discipline no matter what life throws at you. The idea is that you should make your routine as easy as possible to start - meaning it should take no more than 2 minutes to get going. What this does is reduce friction, which ties in directly with what we discussed earlier performance by subtraction. Productivity = elimination (of obstacles). However, I've found it most useful for bad days - when you've mismanaged your time (played too much with the corgi) or when something gets tossed at you unexpectedly). Instead of skipping any parts of my routine, I elect to shorten the time I spend on them:

Side note: I do take weekends off, however - it's like a longer buffer. If I had to actually skip a part of my routine during the weekdays, guess what? I can "make it up" on the weekend - and minimize the risk of burnout. A bad day in the gym is still a day in the gym. Over time, this becomes your identity: You become a person who never skips a day. And whatever identity you have, you'll do everything possible to live up to it. It's much better than having to constantly motivate yourself. Lastly, you can pair certain habits or actions together. For example, during my stretching routine I'll also study my language app on my iPhone at the same time. You've probably done some version of this already - such as doing laundry, washing dishes, or commuting to work while listening to a podcast. Get creative and see what else you can come up with. And if you figure out something cool, let me know! What're You Waiting For?One simple routine can mean the difference between failure or victory, between a productive day, year, or even life. But this only works when you see how each single action you take is connected to the trajectory of your most important goals. One action, one habit becomes a small, but crucial, part of your work day. And the entire routine becomes critical for your success. "We are what we repeatedly do," said Aristotle. You are your actions. In the same vein, your routine is you. So take what you've learned today, put it into action, and prove to yourself the type of person you want to be. I have faith in you. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

This article contains affiliate links … If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

From the book Daily Rituals, by Mason Currey, we learn about the daily routine of - arguably - the most important composer who ever existed:

Beethoven rose at dawn and wasted little time getting down to work. His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose. Then he sat at his desk and worked until 2:00 or 3:00, taking the occasional break to walk outdoors, which aided his creativity. Actually having the patience to count sixty three beans seems unusual, but it didn't compare to his bathing habits: If he did not dress to go out during the morning working hours, he would stand in great déshabillé at his washstand and pour large pitchers of water over his hands, bellowing up and down the scale or sometimes humming loudly to himself. Then he would stride around his room with rolling or staring eyes, jot something down, then resume his pouring of water and loud singing.

You might be reminded of the quote, "genius is one step away from insanity." Like, is it really necessary to go to such lengths just to get some work done? YES. Yet Alex Hormozi, a successful businessman and entrepreneur whose advice I've followed faithfully, says the opposite. He states that rituals are a waste of time. His argument is that they're a form of procrastination, and that you should just eliminate them and get to work. And as much as I look up to him, I completely disagree. I mean, if that were true then Lebron James would never chalk up his hands before every game. Religious people would stop praying. Every superstition in the world would disappear. You see, rituals serve a function. Now, in Hormozi's field of work this function might have no purpose. But for me, a daily ritual has been fundamental for my productivity. And if you're not convinced, pick up a copy of Currey's book. It's hard to argue with 278 pages of proof. So in part 1 of this 2-part series, we'll cover:

In part 2, we'll continue this line of thinking with routines. PurposeFirst of all, what exactly is a ritual? Though your definition might be different, here's mine: a single action, or set of actions (physical or mental) you repeat on a regular basis to prepare your mind for a certain activity. This idea is closely related to an anchor. One example is Pavlov's Dog:

The bell was an anchor for the dog while a ritual is an anchor for your mind. You'll also notice that the definition is broad. And since it's so broad almost anything can be a ritual. For example, something as simple as clipping your fingernails can be a ritual. Like a warrior sharpening their blade for battle (okay, that might be a stretch). It's not so much the act itself, but the intention behind it. Now, let's take a look at the benefits, or functions, of rituals - all of which have an impact on your productivity. Junction, Junction, What's Your Function?The first benefit is control. Your ritual can be something you can do at any time of the day and any place. What makes control so important? Because it's related to your happiness. Lack of control is what makes people miserable. Everyone has stories about jobs they've hated or teachers who made their life a living hell. And besides that, life can be unpredictable. On chaotic, stressful days, a ritual becomes your ally. A good ritual also gets your mind into a certain headspace. Nowhere is this more apparent than in sports. One of my favorite pre-game football huddles was Drew Brees doing his best imitation of Leonidas from the movie 300 - THIS ... IS ... NEW ORLEANS!!!. Every team has a pre-game ritual, every battle chief has a warcry. Now, if your ritual is more elaborate you can create momentum. You're able to "stack" them one after the other, with each part leading directly to the next one. This is the science behind checklists: every item you check off leaves you feeling satisfied, invigorated. But in this case, it's like a checklist for motivation - very useful for days when you can barely get out of bed. You also achieve a process-oriented mindset. This is because the whole point isn't about achieving a certain result or outcome. Rituals are a form of active meditation. There's no endgame or result - it's about practicing awareness. The more present you are during your ritual(s) the more you'll benefit from the calmness you feel. And a calm mind is a productive (stress-free) mind. Lastly, daily rituals are a form of discipline. Over a long period of time, it actually feels weirder when you skip. And for me at least, I've been able to use my rituals as a starting point to maintain discipline in other areas of my life. How to Be Productive: The BlueprintSo here's what I do. I have 2 rituals - one for the morning and one before I begin teaching. I use my morning ritual to signal the beginning of my morning work session and a second afternoon ritual to wind down and prepare for piano lessons. The first thing I do look at my memento mori coin. Memento mori is a Latin saying that translates to "remember you have to die." It's a reminder of mortality and to not waste my time on trivial matters. Next, I journal. What I write about might be different every day. Sometimes I'm just "emptying the tank" so to speak - if I have a lot going on in my life, I just lay it all out. Other times I might be more purposeful, such as planning the day ahead or writing about things that are going well ... or aren't going so well. Afterwards, I get to work. After about an hour or so, and when I feel my concentration waning, I head back to the kitchen for the best ritual of the day ... COFFEE. And I prefer the physical act of hand-pouring 2 cups of coffee (for me and my wife). The physical act is enjoyable and it helps me slow down. It's like I mentioned earlier - active meditation. Then ... more work. After a few more hours, I wrap up my work session and then it's time for my next ritual I head back upstairs to stretch and wind down. While I'm stretching, I use my inside voice to repeat my 3 daily mantras:

I finish up with a meditation session and off I go to teach. Now for some practical advice.. Help, I Need a RitualFirst, do NOT use my rituals as a model. It's something that took me a decade of trial and- error to develop. When I first began, I started small - while trying out many different things - and I suggest you do the same. Secondly, whatever you choose make sure that they will be things you look forward to doing. And third, make sure they're process-oriented, meaning there's no specific outcome you're hoping to achieve. Just take enjoy the action itself. Also, make your ritual something you do first in the morning. By doing this, you prioritize its importance and also start your day off the right way. And don't be rigid, you don't want it to feel like the end of the world if you're not able to complete everything on your list every single time. In fact, plan for bad days to happen. There's been many a time I've had to shorten my ritual or even skip some parts altogether. Tell yourself it's okay if this happens - a bad day in the gym is still a day in the gym. You not only keep the "chain" going but you prove to yourself that you're the type of person who follows their daily ritual without fail. Now, there may come a point when you stop enjoying your rituals. This usually means 1 of 2 things:

If you're bored, then change things up. You can try new rituals or change the order of the one you have. If you're not present, you probably need to release some stress or practice awareness (meditation). Sometimes it's as simple as stopping for a few minutes and taking really slow, deep breaths. Lastly, you might want to incorporate a nighttime ritual. Cal Newport calls this a shutdown ritual. The benefit is it signals your brain to begin getting ready for bed. An example is stopping all work-related tasks at a specific time and unwinding with some light reading or entertainment. As someone with sleep issues, this has been an IMPORTANT step. The First Cut Is The DeepestTwyla Therp, in her book The Creative Habit, says: The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual. James Clear (Atomic Habits) calls this a decisive point. He defines it as the crucial moment before you make a decision or take a specific action. One small action can compound over time, resulting in huge payoffs. And the opposite is true as well - one small, bad decision can create a thousand headaches. Your ritual becomes the entry point to a productive day. With practice, you begin to understand that everything is connected. One simple action starts an entire web of processes. And that process can lead to a great month, year, or even decade. So the next time you finish an important project or achieve a substantial goal, remember that the starting point was your ritual. Lastly, you won't have great results all the time. You can't always control how your day will go, but you can at least start it the right way with a good ritual. Hope to see you back here for next time when we discuss routines. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

This article contains affiliate links … If you choose to purchase, this means I receive a (very) small commission at NO EXTRA COST to you!

I've had my fair share of train-wreck performances, I remember playing passages in the wrong key or forgetting the very first note.

I've also seen colleagues engage in all types of strange rituals backstage. Pacing frantically back-and-forth, repeating mantras over-and-over again, desperately rubbing their good luck charms or facing the corner of a wall and staring blankly into space. The only thing missing was an elaborate seance over a ouija board. Stage fright causes us to act out in all sorts of weird ways and sometimes you feel like it's out of your control. Well, you can do something about it. Let me show you how. How to Overcome Your Performance AnxietyThe Root of Performance AnxietyWhat is it about stage fright that makes it feel so devastating or life-threatening? Well, from a biological perspective ... it's because it's actual fear. For the longest time, humans survived in tribes. And survival meant being part of a cohesive unit - in other words, not standing out. If you did, one of the following two scenarios would have happened:

So we feel this on a subconscious level since our "software" hasn't been updated to the modern times we live in. When we're walking up to the stage, getting ready for a job interview, or preparing for a public presentation, we get locked into this "fight or flight" mode. We imagine the crowd is "against" us. And since we can't run away, we have no choice but to prepare for battle. This is why it's so hard to get out of our comfort zone and why exhibitions feel like life or death. Modernity and Performance AnxietyWe fight against our ancestral tendencies as well as a modern disease: Perfectionism. This is also what fuels our backstage anxiety. Most students aim for a "perfect" performance, which usually means getting every single note correct. This is not only unrealistic, but a terrible goal to begin with. Because even if they succeeded, what would be the result? An accurate but boring, soulless, and robotic performance - while looking absolutely miserable on stage. Not only that, trying not to make a mistake means you actually make more of them. This has to do with the usual advice we get, which is "don't be scared" or "don't be nervous." This makes the problem worse because your mind focuses on whatever's in front of it, good or bad. Don't be scared gets translated into don't be scared. It's like trying not to think of a pink elephant. And the opposite approach doesn't work either. For example, when you're told to "be more confident." For one thing, what does that even mean? If you can't formulate an actual plan then it's just wishful thinking. And secondly, you need reference experiences. If a student has never performed before then this wishy-washy advice won't work. What's even worse is if they've had traumatic public experiences - failing miserably in front of all their peers. No amount of practice can fix this alone. You can try to give them whatever advice you want, but their brain will keep looping endlessly on these disappointments. The Blessed OnesAs if this wasn't complicated enough, mainstream advice can work for some students. But that's because they have a different set-point. Let me explain: I am in no way a naturally happy person - most of the time I'm brooding or lost in thought. Does this mean I'm depressed all the time? Not at all, it just means my happiness setpoint is lower than average. It's almost like my standards for being happy are higher (don't judge). So if you have a naturally jubilant friend who never seems to be in a bad mood, her setpoint is likely way above normal (or she's a psychopath). When these vague suggestions work, these students most likely have a higher "confidence" set-point. For example, I have at least one student who tells me she's never been nervous for a performance - even when it was her first time(!). It’s All GoodNow, one effective way to overcome stage fright is to learn the art of the reframe. Reframing is interpreting something in a different (negative or positive) way. It's like how some people have everything in life but always think "the grass is greener on the other side." This is explains why two people can look at the same situation but have completely different reactions to it. Road rage is one example - ever had someone flip you the bird for something you didn't do? So instead of avoiding fear, tell yourself it's okay to be nervous. Even better, it's good to be nervous. Doing so creates acceptance instead of resistance. It's good because it shows you care. Think about it for a second, if you weren't nervous at all then you could miss damn-near every note and not give a hoot. You would have questionable character, but not a shred of anxiety. Now, the amount of nervousness is going to differ for every student. Besides their setpoints, this is usually caused by a lack of experience. The less experience you have, the more nervous you'll feel and vice versa. As a side note, I actually believe that your nerves never go away. When you gain more experience, you just get more comfortable with the feeling of nervousness. NextThe following strategies I'm going to lay out for you are meant for the first-time performer but can be adapted for any level. Before we get into the specific plan, let's first talk about mindset - because the best advice in the world won't work if you believe you're going to fail. Earlier, I mentioned how detrimental the perfectionist mindset is. Along those lines, believing and imagining you'll be 100% successful isn't good either. Why? Because a first-time performer has no idea what's going to happen. For example, if a student has been visualizing their ideal performance going off without a hitch, what's going to happen when it doesn't go as planned? When they're confronted with an alternate reality than the one they've created, the results can be disastrous. The better approach is to expect mistakes since this is what's most likely to happen. This is to do is get them out of their heads. Bad performances occur when the students make the whole experience about themselves. It's understandable, but too self-important. This is how amateurs think, while professionals put themselves in the shoes of their audience. They obsess over how their fans are experiencing the entire event. One way to help them understand is by asking them to pay attention to what the other recitalists are doing - usually staring off into the abyss. The message I hope they hear is that everyone is just as nervous as they are. I also help them realize that the crowd actually wants them to succeed. Think about it, what kind of demonic people would want a grade-schooler to crash and burn? The PlanBy now, the student has hopefully developed a more positive attitude and expectation towards performance. Once they're fully bought-in, we can start planning and preparation. But first, an important concept: encode success. I stumbled across this idea from the book Practice Perfect. The basic gist is to make success is inevitable. But what does this mean? As I've been repeating over-and-over again, success is NOT a note-perfect performance. It's the student enjoying the process as much as possible, overcoming any setbacks or challenges, and avoiding traumatic experiences. The ultimate goal is for them to look forward to the next (every) recital. So far, the success rate is 100% (humble brag). And for this to happen, the preparation is designed to help each student succeed in the easiest possible way. One way is to pick a goal they can understand and achieve - like not giving up. They can forget notes, play the wrong rhythm, get lost in their music ... it doesn't matter as long as they make it to the last note. Mission complete. Two other ways are picking sheet music they've been playing for a long time or having them play in the program as soon as possible, since waiting too long can be stressful. Additionally, recital preparations are began as far ahead as possible - usually 3 months before their first performance. And even if it's not the student's first time playing in public, we want to do this anyway. This is because I only organize 2 recitals per year. Since there's a lot of downtime in between these events, it's necessary to plan ahead because fewer opportunities magnify the pressure they feel. As a side note, if the student has more performance opportunities throughout the year, you can sidestep a lot of these suggestions and learn through simple trial-and-error. But this concept still helps. Action

We now know that stage fright is created because of our ancient biology and perfectionist mindset.

Earlier, I mentioned another reason is that the student doesn't know what to expect. So the best way to plan for the unknown is through rehearsals. We "rehearse" what will happen for sure:

And of course I provide a healthy amount of loud, enthusiastic applause. We'll practice this sequence as much as humanly possible, until they no longer have to think about it. Why do these simple actions help? Because it gives the student a sense of control. These are the things they can accomplish no matter how their actual performance goes. This helps develop stage presence, i.e. how comfortable someone is under the spotlight. Ideally, instead of focusing on their nervousness they'll simply complete each action - like a checklist. Now once they're comfortable, I increase the challenge by recording them. Just like they say the camera adds ten pounds, this creates a heavier atmosphere. We make the rehearsals more difficult to make the actual performance easier. But let's say the student is still stressing out and putting too much pressure on themselves. In that case, I'll have them practice failing. The goal is for them to actually make mistakes. For example, if the student makes 3 errors - and I've ask for 5 - we've failed to accomplish this task. They begin to understand that mistakes are part of the process and have more fun making them. But here's the kicker: they have to practice overcoming any rough spots. The ability to get out of a tricky situation is the most important skill they'll need on stage. Lastly, I tell them that the preparation is more important than the actual result. If they've put the work in, what happens at the recital doesn't matter - at least to me. ConclusionBefore you go, I want to leave you with a few more suggestions. Piano performance isn't the only way to overcome performance anxiety - think of any public venue as an opportunity to practice. Try striking up a conversation with a complete stranger - if that sounds intimidating pretend you're asking for directions or suggestions. You can also join your local Toastmasters to practice public speaking in a supportive environment. Opportunities abound and the more experience you wrack up the more overall confidence you'll have. You'll be able to refer back to these encounters with the knowledge you've succeeded in the past and can do it again. And if you're serious about your piano practice, performance is something you must go through. What's the point of practice if you don't share your progress? That's like me writing this blog post and never publishing it. So I hope you've learned something about stage fright today, or even changed the way you approach it. Remember to set the bar as low as possible and be satisfied with any amount of progress you make at each juncture. Use what you learned today and I hope your next performance will be a great one. Happy practicing!

Did you enjoy reading this today?

Your donation helps me create free content. Every dollar goes a long way! =)

|

Categories

All

|